County Wide - He enters computer age at 93, but recalls when chips

were down. R.H. Growald

The San Diego Union-Tribune 2 June 1988

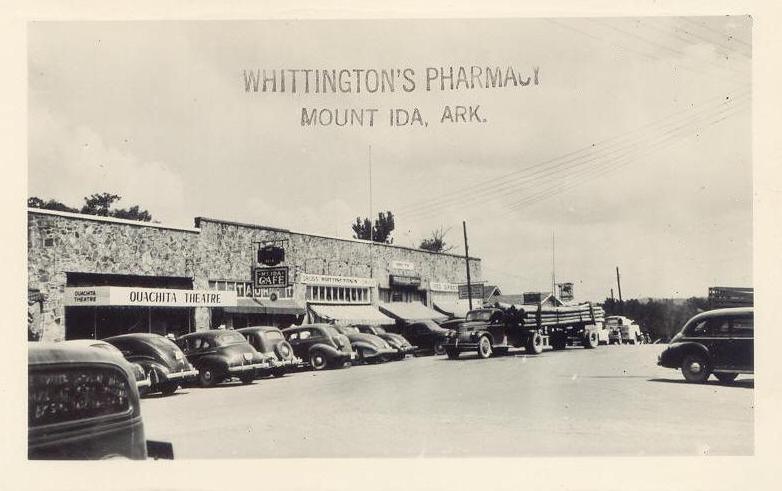

Harry Standefer just bought a computer for his 93rd birthday. Built as straight and almost as tall as the piney woods back in his native Arkansas, Standefer fans his right hand fingers across his face. He estimates costs for building contractors. He figured the computer would make all the numbers as comfortable as life back in Mt. Ida. "I dunno," Standefer says. "A computer is like Mother Nature. You got to do things her way. "Back in Mt. Ida (Standefer has been out of Arkansas 45 years but pronounces his hometown as Mount Eye-Dee), back in the one-room school, we didn't even have paper and pencils. "We had slates. A 12-by-18-inch slab of slate in a wooden frame. You wrote on it with a little piece of slate." In Mt. Ida, a skyscraper was two stories high. "Papa taught seven grades, sometimes eight, in a one-room school. I grew up to be a teacher and taught in one-room schools. Fact, I was born in a one-room log cabin," Standefer says. "Mama and papa raised us nine kids -- I was the oldest -- in a one-room house there in the Ouachita Mountains." Standefer says his father finished the fourth grade and, later, secured a teaching certificate. His reward? "At first they paid papa with an occasional hog and cornmeal. By the time I was born, he was making $25 a month," Standefer says. "School was five months a year. July, August, November, December and January. Rest of the time kids were out helping with the crops." And there was adventure. Standefer, at 2, had a horse fall on him. He remembers the fox tracking the sow to the log cabin's front door. And the frozen winter he had to ride to the doc's house in Buckville. His baby nephew, Esmond, was ill. Standefer borrowed a horse at the town of Bear and rode for help. At a crossing, the horse plunged into the icy Ouachita River. "We went under. We got washed downstream. But we got out and the doc built me a big fire at his house in Buckville and gave me medicine and a coat and I rode back.

"Little Esmond is now a retired professor of agriculture in Conway," Standefer says. He was 15 when he saw his first car. "It was a chain-driven Sears & Roebuck. It was the pride of Hot Springs. But the greatest sight was the cookstove," he says. Standefer in later years worked for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. One of his sons was a chief constructor of Washington's subway. But, ah, the coming of the cookstove. "Until 1904 mama did all her cooking in the fireplace. Papa brought home a cookstove, fueled by wood. Mama had to learn cooking all over again, how to use an oven and cook on top," he says. He says she cooked the same cornbread and stews of her fireplace days. Standefer and his wife, Ella, who is 94, survey their San Diego kitchen. It has a microwave oven, gas range, pressure cooker, toasting oven and the other badges of the era of quiche and brie and zucchini. "Ah, but I believe nothing tastes so good as it did back in Mt. Ida," he says. He first saw the world beyond the Ouachita Mountains in 1914. "That year I rode the freight cars to get work helping in the wheat harvest in Kansas. I lived with the hobos. I got jailed for vagrancy for one night in Joplin, Mo. Mt. Ida seemed sweeter," he says.

Then came World War I. Standefer grins. "For me it was almost a paid vacation. They drafted me in 1918. Training was interesting if brief," Standefer says. "Five weeks after induction I was aboard ship for France. They had given us a rifle-range test. "Now I grew up with a .22-caliber in my hands. And with granddad's squirrel-hunting cap n' ball rifle. When I set that Army rifle against my shoulder, it had found a home." He shot so well the Army promoted him to corporal, then sergeant and made him an instructor with the Browning automatic rifle. In France, Standefer never came under fire. But his gold-handled penknife did. "A fellow soldier named Armstrong borrowed it before going to the front line. I never saw it again until I was being discharged in Camp Pike, Ark. I met Armstrong. "He gave me back the penknife. Poison gas had turned the gold green," he says. Standefer's eyes twinkle; he is remembering Paris. "I had a two-day leave to go to Paris. On the train a buddy and I saw two lovely English army nurses. They were sitting facing two U.S. sailors. "I stared all the way to Paris. I told my buddy we should date them. My buddy was ready to face the Germans but two beefy sailors," Standefer says. "At the Paris railway station I pushed through the crowd and got ahead and turned and blocked the path of the loveliest of the two English nurses," he says. Sgt. Standefer: "Woman, for God's sake, say something to me." English nurse: "What should I say?" Sgt. Standefer: "Anything you please. Just say it in English." Standefer, who had not met an English-speaking woman in months, escorted her to dinner, to the opera, to lunch, to a vaudeville show and to Notre Dame. He wonders if his artwork remains on the cathedral. "I paid a keeper of Notre Dame to let me and the English nurse climb to the roof. There, on the sandstone, I carved our initials," he says. "I suppose the initials are there for eternity."

He pauses. He turns to his wife. He suggests perhaps their five children, 10 grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren are a more enduring testament. Standefer kisses his Ella.

Is Samuel H. Sandefer (b.

1888) in the SSI database?

Obit.

Died March 1, 1993, aged 97.

1900 census Montgomery Co.

Caney Twp

Bio

Harry Standefer

Spelling variations

Standefer

Standifer

Standiford