Charles Pitney Alley

1919 - 2008

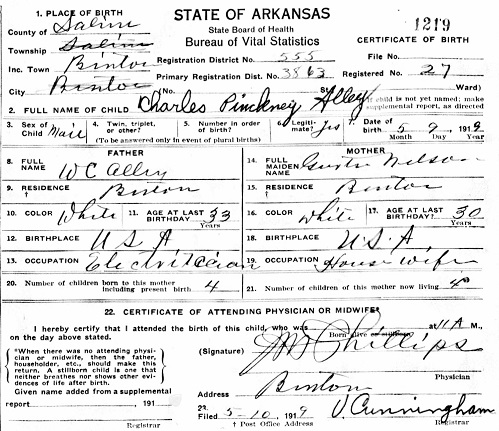

Charles Pitney Alley was born May 9, 1919 in Benton,

Saline Co., Arkansas to Calvin William and Gertrude Alice Nelson Alley.

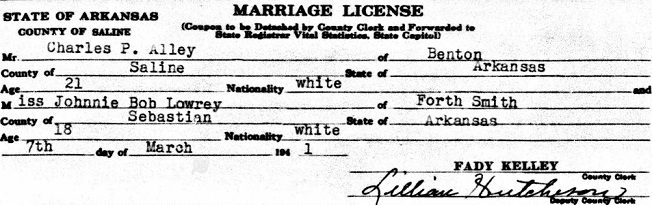

March 9, 1941 he married Johnnie Bob "Jaybee" Lowrey in Saline Co., Arkansas.

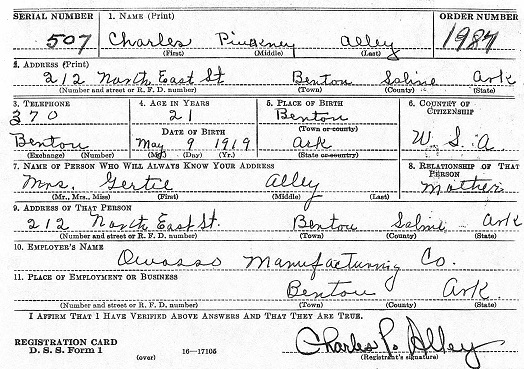

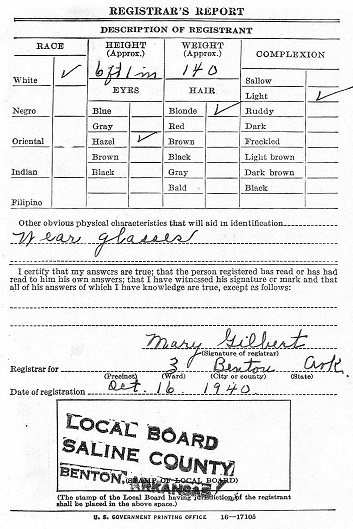

Oct 16, 1940 Charles registered for the military draft in Benton, Saline Co., Ar.

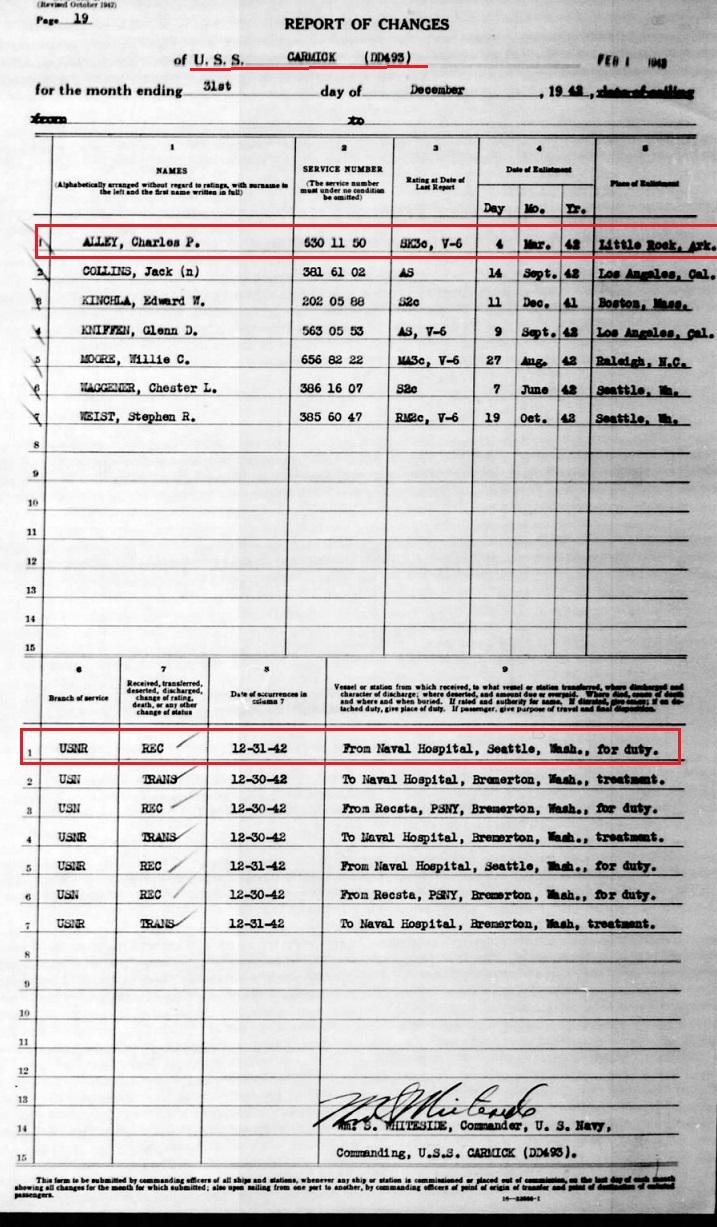

March 3, 1943 Charles enlisted in the US Navy in Little Rock, Arkansas. The

details of his time in the Navy during WWII can be found at the bottom of this

infomatiton from a personal interview with the Fort Smith Historical Society.

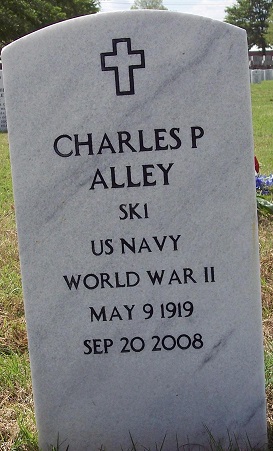

Charles Pitney Alley passed away Sept 20, 2008 and is buried in the National Cemetery at

Fort Smith, Sebastian Co., Ar.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~`

Find A Grave

Charles Pinckney Alley, 89, of Fort Smith was born May 9, 1919, in Benton to

Calvin William and Gertrude Nelson Alley and died Sept. 20, 2008, in his home.

He was preceded in death by his parents; three brothers, Paul, James and Lee

Joe Alley; two sisters, Jean Adams and Nona Spradling; and a son, Gary Alley.

Mr. Alley enlisted in the Navy at the onset of World War II and was a storekeeper

aboard various destroyers in the Pacific theater. He was a member of First

Presbyterian Church of Fort Smith, the Benton Arkansas Lodge No. 34 F and AM

and the American Tool Association. Mr. Alley was in the furniture manufacturing

industry for many years. He began his career with Owasso Furniture in Benton.

In 1957, he moved to Fort Smith and joined Flanders Manufacturing as vice president

of production. In 1972, he founded and was president of Designers Furniture in

Van Buren. After retirement, he was affiliated with Calvin Alley and Associates.

Mr. Alley was an avid and knowledgeable collector of antique woodworking tools.

He donated his time to provide a special selection in the Fort Smith Museum of

History to display his collection of antique wood working tools, recognizing

the significance the furniture manufacturing industry was to Fort Smith's history.

Private family burial will be at U.S. National Cemetery. A celebration of his

life will be 11 a.m. Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2008, at First Presbyterian Church

officiated by Dr. William Galbraith. Family will greet visitors following the

service. Arrangements are under the direction of Edwards Funeral Home of Fort

Smith.

He is survived by his wife of 68 years, Johnnie; one son, Calvin Lowrey Alley

and his wife Marilyn; one daughter, Trude Moore and her husband Dennis of

Fayetteville; five grandchildren, Chris Alley of Bella Vista, Sarah Curry

and Justin Moore of Fayetteville and Duayne and Charles Alley of Fort Smith.

Memorials may be made to First Presbyterian Church, 116 N. 12th, Fort

Smith, AR 72901; Peachtree Hospice, 4300 Rogers Ave. No. 33, Fort Smith,

AR 72903; or the Fort Smith Museum of History, 320 Rogers Ave., Fort Smith,

AR 72901.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~`

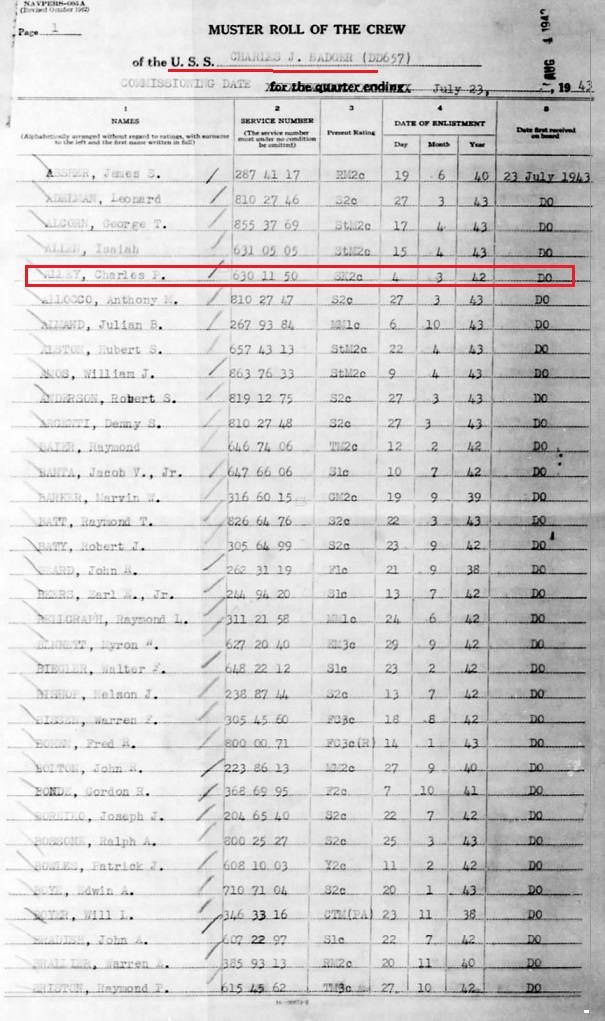

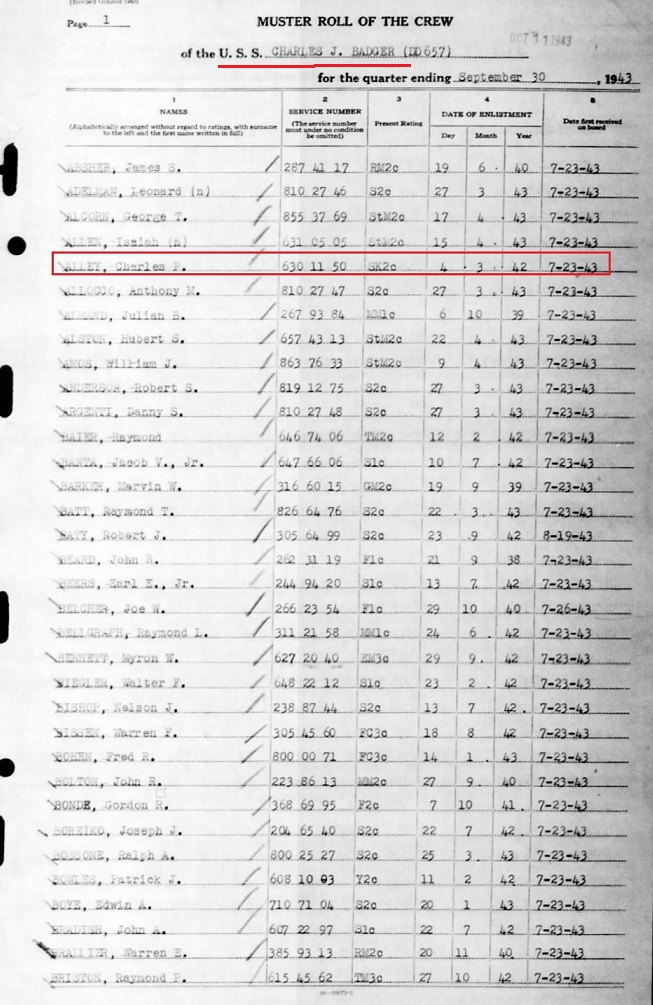

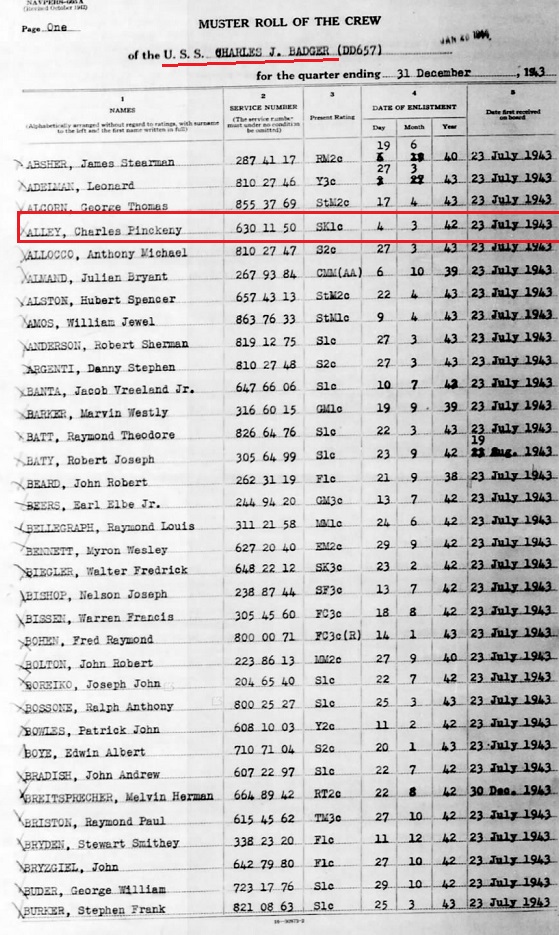

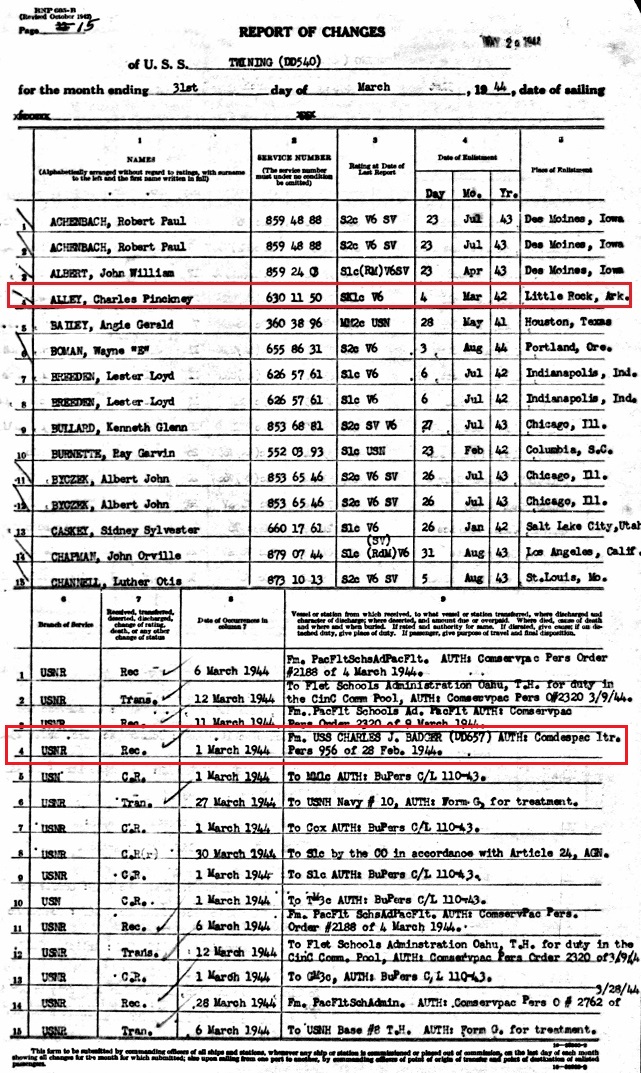

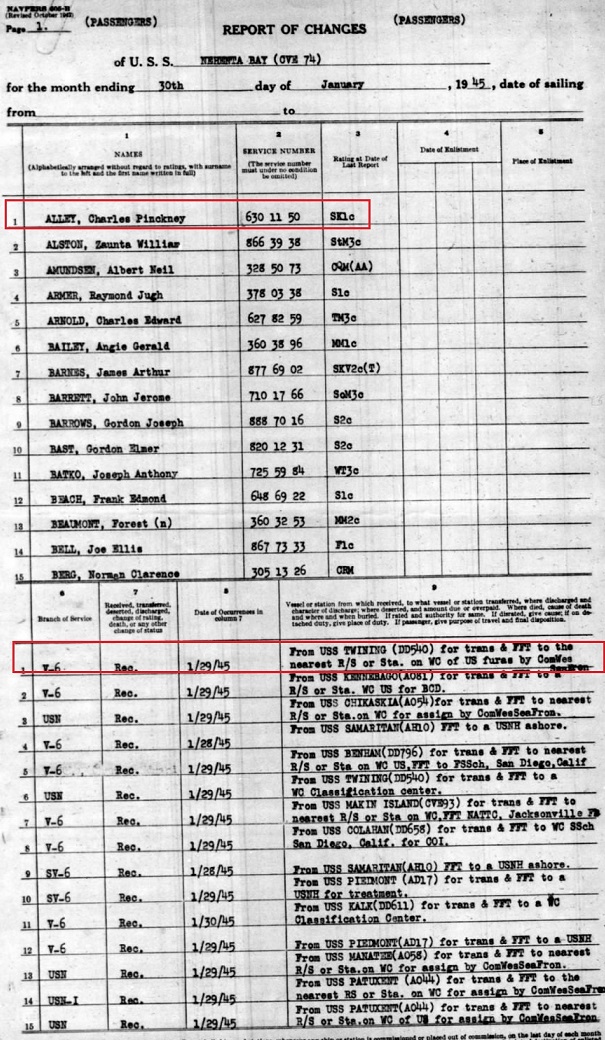

Some of his US Navy Muster Rolls are below the interview.

Since Charles served on several ships. I've put a link above a muster page

that will tell you when and where each of them were

in battle and some details of each one, showing their movements and history

in WWII.

World War II Veterans History Project

The Fort Smith Historical Society

Interview with Charles Pitney Alley

http://fortsmithhistory.org/index.html

CB: Mr. Alley, if you would give us your name and spell your last name and tell us your birthdate, please.

CA: All right. Name is Charles, P for Pitney, A-l-l-e-y.

CB: And what is your birthdate?

CA: (DELETED CONTENT)

CB: (DELETED CONTENT)

CA: That's right.

CB: Thank you. Where were you born?

CA: Benton.

CB: And what county is that in?

CA: That's in Saline, right next to Pulaski.

CB: And what were your parents' names, please.

CA: My dad was Calvin W. Alley, and my mother was Gertrude Alice Alley.

CB: What was her maiden name?

CA: Her maiden name was Nelson. Actually her father was Neilson, but they Americanized the name by the time she was born.

CB: What were you doing before you joined the service?

CA: I was in furniture manufacturing production for a large plant in Benton.

CB: Were you enlisted or did you--

CA: Well, the Draft was about to get me so I joined the Navy so I could stay

out of the trenches.

CB: When did you join the Navy?

CA: 1943, March 3rd, March 3rd, '42.

CB: 1942, okay. And where did you go from Benton?

CA: Well, I enlisted in Little Rock, and I left a week after I enlisted on a train to San Diego, California.

CB: You went through boot camp in San Diego?

CA: San Diego, yes.

CB: What were your experiences there in boot camp?

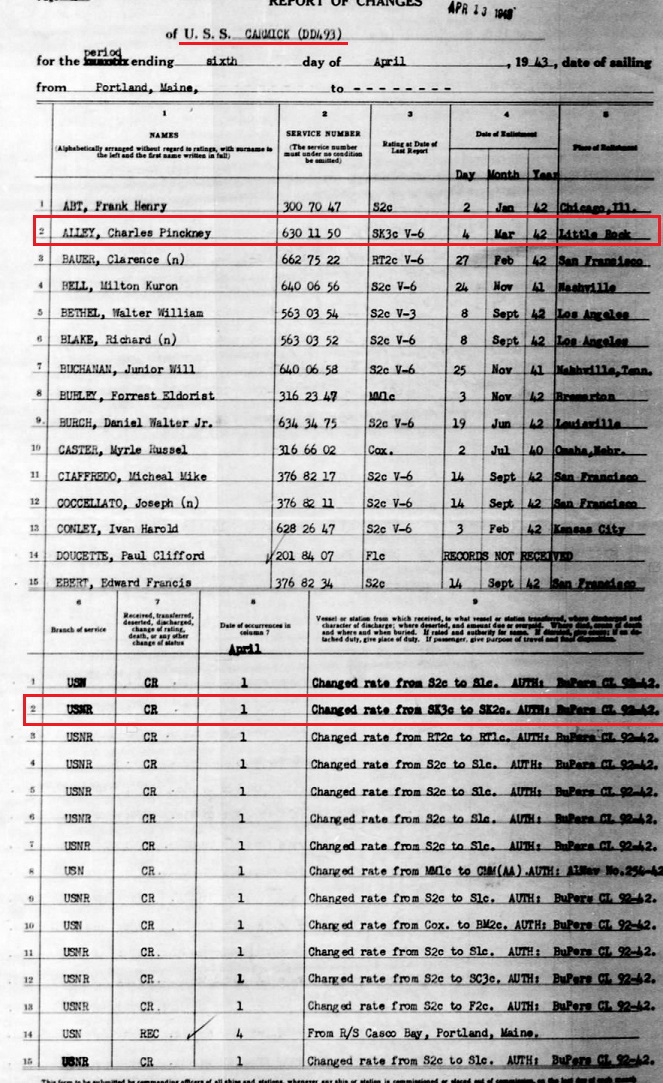

CA: Just a lot of marching, marching, marching. I enlisted as a storekeeper, 3rd class, and that was equivalent to a Sergeant in the Army.

And from there, I was transferred to Seattle, Washington. And from there, I went aboard new construction, it was the USS, they had the

TWINING and CHARLES BADGER and the other name, I can't even think of it, CARMACK, C-A-R-M-A-C-K.

CB: Now what was that?

Daughter: That was a destroyer, all of his service was on a destroyer.

CB: And you went aboard the CARMACK in Seattle?

CA: Yes, uh-huh. And took it through the canal zone into the Mediterranean, and on into New York, all the way up to New York.

Then we went up to Portland, Maine, which is--

Your convoy duty in the Atlantic, Dad.

CB: Convoy duty in the Atlantic?

CA: Atlantic, yes. It's hard for me to remember all this. I blocked it from my mind.

CB: And it was so long ago.

CA: We was in on the African invasion, which that was in North Africa, and we handled convoy duty and anti-submarine demolitions,

you might call them.

CB: What would that mean, what did you do in anti-submarine?

CA: We dropped depth charges, mainly, on submarines, depth charges and hedgehogs. Hedgehogs were pushed out from the side of our ship,

and the depth charges were just big barrels of like an oil barrel today, but full of dynamite, and they were set to go off at certain depths.

And that first attack, we crippled the German submarine fleet off of Africa, they lost a big majority of their submarines there from us. We

were troop ships, is what we--

JW: Did it occur like we've seen it in the movies? Did you know you'd hit a submarine because of what came up?

CA: Well, yes; but course, they tried to fool you, too. They'd push up garbage so it would surface and makes me think we got him, he's

dead in the water. But you could pretty well tell whether you got them from sonar equipment we had, and we were very successful in wrecking

their submarine fleet.

CB: How large would that fleet have been?

CA: Probably fifty or sixty ships of all types. We'd have carriers, battleships, cruisers and destroyers.

CB: Now, that was the U.S. fleet?

CA: That was the fleet in the Atlantic at the time. It was just a Task Force they called them, but most of the action I was in is in the Pacific.

It was just anti-submarine warfare off of Africa and up in the North Atlantic, too.

CB: But that's where you went first?

CA: That's right, that's right, my first battles.

CB: And what did you do on the destroyer?

CA: Well, I was a storekeeper. I was in charge of all purchasing of everything except medical supplies, and the doctor purchased those,

and munitions. The captain of defense, he bought his own munitions

JW: And this was on the CARMACK?

CA: That was on the CARMACK, uh-huh.

Daughter: He was a storekeeper on all three ships that he was on, it was the same duties on all three ships.

CB: How much battle experience did you have?

CA: Well, not a lot in the Atlantic. But then we put a new ship in commission in New York, and Johnnie was able to come up there with me,

but she got pregnant. But after those submarine battles, I went back to the Pacific.

CB: When would that have been?

CA: With a new ship, that was the second ship. Was on the CARMACK, and I was transferred to new construction it was called, and the

ship was being built on Long Beach, Long Island, and I went aboard it as my first sea duty. No, it wasn't my first sea duty, it was my

first new construction, although I was on the CARMACK in the Pacific, it was new construction. But I got sick and went in the hospital

and I didn't get to go aboard it as a new construction sailor. When you went aboard a new ship, you owned a plank in the ship, they all

said you was a plank owner. And all three ships I went on, let's see, were they all three new? No, no, we went back to the Pacific on the

second ship.

CB: What was that named?

CA: CHARLES J. BADGER, B-a-d-g-e-r. br>

Daughter: You want dates on that?

CB: It would be nice.

CA: This starts this diary more or less that I kept there. It's not too much of a diary, it's more of a record.

CB: You kept this during the war time?

CA: Oh, yes, uh-huh. I was in New York on August 12th, 1943. And I was in New London, Connecticut, a little later; I was in

Portland, Maine. Went to Bermuda aboard the ship and this is mainly training, except for when we ran across submarines. And

from there, I went back down the coast and went back to the Pacific.

CB: And this was on the CHARLES BADGER?

CA: CHARLES BADGER, uh-huh.

CB: Did you go through the canal this time?

CA: Yes, been through it twice. And I was a material buyer, food buyer and everything. I never got to go from the dock into a warehouse,

I never got to see the canal. We saw it when we was going through it.

CB: Where did you end up on the Pacific then as you returned?

CA: Yeah, I was in the Atlantic until November of '43. And I took a new ship, the CHARLES J. BADGER, back through the canal,

and we operated out of San Francisco and I ended up in Pearl Harbor from San Francisco. And my wife was with me some of that

time, shore duty there. Weren't you with me a little in the Atlantic, I mean Pacific?

Daughter: That was before you went aboard ship, when you were training.

CA: I went through the Panama Canal in November of '43. And out from there, I went to Pearl Harbor; now I'm getting it straight.

Went from there to Adak, Alaska. Adak, you got a string of islands going down in the Aleutians and Adak is the furthest island.

CB: How do you spell Adak?

CA: A-d-a-k. And from there, I went to Dutch Harbor.

CB: Now what were you doing there?

CA: There, we were training mainly, unless we ran across submarines.

CB: Did you run into Japanese submarines?

CA: No. When we was going to invade Adak, Alaska, because the Japanese were there. And we got our fleet ready and we got our troops

on board and we rushed ashore, and the Japanese had all left two days before. Japs took them all off in submarines. But we thought

we were going to have a big battle there, but we didn't catch them. Those two days, they were loading.

CB: There were a lot of Japanese troops up there.

CA: Oh, gosh, yes.

CB: And they got them all out?

CA: Got them all out. We had an empty island.

CB: Well, what kind of damage had they done in Dutch Harbor, the Japanese?

CA: None, that I know of.

CB: They had been through there?

CA: They didn't get up to Dutch Harbor. They only had Adak, which is the furthest on that island chain.

CB: Well, that's interesting.

Daughter: When did you go aboard the TWINING, Dad?

CA: But I spent a whole winter in the Aleutian Islands. And that weather was so terrible up there that they say if you fall in the water,

you fall off a ship, just forget him because he's dead almost immediately when he hit the water. It was just beat up ice all around the ships.

CB: What did you do that winter in the Aleutians?

CA: Tried to keep warm. I know I was a look-out watch on the bridge; and night or day, you couldn't see six feet in front of you, it was so

cold and so frosty.

CB: Did you ever see anything?

CA: No, you couldn't see anything. We'd go on watch off the bridge, which is the high part of the ship, and keep us out there five

minutes and we'd go in and knock the ice off of ourselves and we had five minutes inside, then you had to go out another five minutes.

And I often wondered why because you couldn't see anything, you couldn't see anything, just cold fog about six feet out in front of you

maybe or three feet.

CB: How many men were up there with you?

CA: You mean how many men on my ship?

CB: Well, were there other ships?

CA: We operated pretty independently up there, and our ship had three hundred and thirty men on it. And from there, we went to Pearl Harbor

.

Daughter: Is that where you got on the TWINING?

CA: Yeah. I transferred at Pearl Harbor from the CARMACK-- from the CHARLES BADGER, transferred in February of '44 is what it says here,

transferred to USS TWINING.

JW: And how do you spell Twain?

CA: T-w-i-n-i-n-g.

JW: And it was another destroyer?

CA: Yes, uh-huh. And went to Pearl Harbor just for a training period there.

CB: What training did you have there?

CA: It was anti-submarine duty because there was no enemy ships anywhere around Pearl Harbor after they bombed it.

JW: Was that like a break-in period for this new ship also?

CA: Yeah, training the crew. And two trips made through the Panama Canal was training, but it was on different ships.

CB: What kind of duty is anti-submarine, what would you be doing?

CA: Well, you have sonar and radar on the ship. Radar gives you anything on the surface, sonar gave you underwater soundings.

And it was just to train the personnel to recognize the proper sounds and to recognize the speed and the depth.

CB: You said something about having depth charges and hedgehogs. And what is a hedgehog?

CA: A hedgehog, they are depth charges but they're shot off the side of the ship on what they call a key rail and they'd throw

them way out in the air, away from your ship because you didn't want to sink your own ship. And depth charges were just barrels

of dynamite that was rolled off the stern of the ship.

CB: But basically, they were the same construction?

CA: Well, the ones off the stern were drum size, that big; and the hedgehogs were just little old things about that big around, and had a

key shape. When they went off there, they were shaped like this and this was your dynamite and the charge is back of them. That was only

defense we had in the submarines was those two objects.

CB: Well, they were pretty affective, weren't they?

CA: Oh, yeah; if you could find them.

CB: Did you accompany some battleships or carriers in the Pacific?

CA: I'm just looking here, yes, uh-huh. We formed a Task Force on the west coast and it consisted of a hundred and twenty destroyers,

twenty-two battleships, twenty-five carriers, twenty cruisers; it was the largest Task Force ever assembled in the Navy.

CB: Tell me again. A hundred and twenty what?

CA: We had a hundred and twenty destroyers, twenty-two battleships, that's the big ones, twenty-five carriers, aircraft carriers, twenty

cruisers; they say it's the largest assembly of any Navy in all time.

CB: Who was the Commander?

CA: Well, we had several commanders. Admiral Halsey, Bull Halsey, was his nickname, probably heard of him. He was the commander of the Pacific

Fleet and the men loved him. He came up from apprentice seaman, never went to Annapolis like all the other admirals did, and he talked like a

sailor. He'd get on the radio when we were out there fixing to make an attack and he'd tell us exactly what we're doing. He said, "Now, go out

and kill the son-of-a-bitches." But he was that plain spoken, sailors just loved that.

CB: They loved that. My daddy did, I can remember he just loved it. Did you ever see him personally?

CA: Yes, I saw him. We'd tie up to take fuel on from his ship, which was a cruiser or a battleship, and he'd take exercise and I'd be

on the bridge looking right down on him. He was just going back and forth all the time, and he'd wave, he was real friendly, he was a

sailor's sailor.

CB: This Task Force proceeded off. What time was this now? This was after-- Be late '44?

CA: It was formed in June of '44, I believe it was. Yeah, June of '44.

Daughter: Did your ship join that fleet?

CA: Yes, we joined it. And from there on, it was the big battle in the Pacific against the Japanese. And we were in all the island hopping,

we called it, with that big fleet. And Saipan was one of our biggest battles and we killed seven thousand five hundred Japanese by count.

And I think it was about five thousand Americans also lost in the Battle of Saipan. But that was the beginning of our jumping from island

to island, on up to where we got to Japan. And I left before we got to Japan. As I say, I was due for rest and recreation and I was

transferred back to the States.

Daughter: What date was that, what date did you come back?

CB: You stayed out from about June of '44. Did you get back by Christmas?

Daughter: He got back to the States in March of '45.

CB: Well, how did you feel about that, getting home again?

CA: That was great. Had a son, I met a son that was a year and a half old. He wouldn't have anything to do with me for a long time

because he'd been around women only. He didn't know anything about men.

CB: Tell us a little bit about some of the battles in the Pacific while you were with the Task Force.

CA: Well, it was mainly aerial battles. Sea battle, ship to ship, we was awfully far apart. In other words, we could barely see the

Japanese fleet when we was after them or they was after us. It's hard for me to remember all this stuff; but on Saipan alone, I notice

here when we invaded, that we killed fifty-seven hundred Japanese died on that island, and around four thousand soldiers, Marines,

mainly Marines. The Marines were really noted for going ashore and fighting battles more than the Army, they were just better trained.

CB: I'm trying to remember what battles you would have been in after Saipan.

CA: Well, I came home, as I say before, because I'd been out there so long, came home. But most of the battles I was in was aerial

battles. I noticed here one day, I made a note that we had downed four hundred, we thought we had downed about three hundred planes

of Japanese in one battle. And actually, the count was four hundred and fifty-two planes shot down in one day, and we lost only twenty-one.

CB: How do you account for that?

CA: How do you account for it? We just had superior planes and we had superior pilots. The Japanese had lost all their experienced

pilots, and that was before they went into kamikazes, landing their planes, I got out of there before that. But my ship didn't, my

shipmates later told me all about it. That air raids, those planes diving on your decks.

CB: Unbelievable.

Daughter: Tell her about what you saw on Saipan.

CA: Well, Saipan, we happened to see it on the TV here a couple of weeks ago. That was a terrible battle. Like I say, they lost

five thousand seven hundred and we lost four thousand something. And they used our destroyers, we anchored up just as close to land

as we could, which was very close. We could see tanks battling on the island and they used us as artillery, our radio man and their

radio man. And he would tell our gunners to raise their sights so many degrees and then shoot so many degrees left of where you're

shooting. Now open up, they'd say, because we could hit the Japanese then real good And the Battle of Saipan started at one end of

the island. The island's twelve miles long and eight miles wide, and we drove the Japanese from one end of that to the other, and it

was a hellacious battle. You know, together, we lost thirteen, fourteen thousand people in a week's time. And we finally drove on up

to the upper mountainous end of the island and we had moved over to outside that end and was shooting planes mainly and shooting on land,

too, as to where they were concentrated. And they finally got all the Army up to that one mountainous end, and the civilians, there

was a city on Saipan named Tinian. And we drove through and conquered the town and soldiers all were pushed upon this upper end, and

they were actually jumping off into the sea or into the rocks.

CB: The Japanese soldiers?

CA: Yeah, they wouldn't, they wouldn't surrender, they never surrendered. And they had driven the people of Tinian up to those islands,

and we watched soldiers jumping off into the water and into the land. And then finally civilians, women throwing their children off because

they had been taught that we would rape all their children, and you know, kill the wives and rape their wives and they had been taught that.

And those civilians went up there and jumped into the sea and slung their children in before them. We could see a lot of women just slinging

their children out and then they'd jump. It was a horrible scene because you knew that these people were innocent. Just from fear that they

was going to be tortured. Yeah, we saw it on TV here just a couple of weeks ago, just the way I had described it to her. The mothers throwing

their children into the sea.

CB: How do you spell the name, the people were from Tinian? How do you spell that?

CA: Tinian is-- I'm just not certain because see, Japanese, they had conquered that land. Tinian then, as far as battles, we didn't change

fire with the Japanese ships, they were being attacked by our planes. That's where we got four hundred and something of them in one day. The

sky was full of falling planes. And course, we were shooting at the planes, too; but we had superior manpower and guns that we succeeded in.

CB: I don't know how you could even think in a situation like that.

CA: Well, you think, you hid places behind your stacks. I used to hide places behind the stacks because, oh, I was talking and I'd jump out.

If a shell ever hit a stack, top of the ship would be gone; but you felt a little safer, you know, with a thin piece of metal in front of you.

Daughter: Tell them about your officer that ate a cigarette during some of that.

CA: That was an officer that I was pretty close to. And saw a plane coming, everything was calm, we was at general quarters and I saw a

plane flying right ahead, flying right to us and he dropped a bomb fifty feet off our bow. And I was up there with this officer and I looked

around at him, and we'd been at ease. And he had eaten a cigarette and it was all over his mouth. And that man, he wrote a book, trying to

look for it, it's up there. He was the head of some big company here and he wrote a book that's called "Up the Organization." And I wrote

him a note and told him I had the book and he remembered me, he remembered eating his cigarette.

Daughter: How about the typhoon?

CA: Well, the typhoon was the worst day of my life as far as Navy ships. We had a typhoon.

JW: Was this in the Indian Ocean, in the China Sea?

CA: This was in the China Sea.

JW: We talked to a man the other day that was in the same typhoon.

CA: Our squadron consisted of three ships; the HULL, the SPENCE and the MONAGHAN.

CB: Spell that last one again.

CA: Monaghan.

Mrs. Alley: Monaghan, wasn't it, Charles? Be h-a-n instead of h-a-m.

CA: The typhoon hit us and six ships in our squadron, the HULL, the SPENCE, the MONAGHAN and the TWINING, and I forget the other two ships.

But the typhoon sunk the HULL, the SPENCE and the MONAGHAN. We lost eleven men, that was the worst casualty the Navy ever had as far as weather.

CB: Lost how many men?

CA: Lost eleven, lost all but forty-six crewmen on three destroyers, they just disappeared. We bailed water above the deck all the time,

but we wasn't scared because they always taught us destroyers wouldn't turn over; but these three turned over.

Mrs. Alley: And tell about why yours didn't turn over. Tell her why yours did not turn over.

CA: Well, the day before the typhoon, we were all refueling. We had to refuel at

sea from carriers, battleships or cruisers, big ships. And we'd go alongside them

and booms, put hose lines between the ships, never stop, but they would pump oil

into our ships. And the day before this typhoon hit, we finally got fuel. No, it

was the morning before the typhoon hit, it hit in the evening. And the HULL, the

SPENCE and the MONAGHAN did not get their fuel, and we lost them that night,

completely, and forty something sailors out of eleven that lived. That was th worst

day in naval history as far as weather is concerned. They just disappeared.

We picked up one sailor and he said-- he was the only one saved on his ship.

And he said the ship started rolling so bad, and said it finally-- where it

was on the starboard side and then it just flipped over and sunk. But that was

the greatest Naval tragedy of weather that the Navy had ever suffered and probably

will never suffer again.

Mrs. Alley: It was because the ships sank for lacking of fuel, is that right,

Charles?

CA: The ones that sank did not have their fuel. We got ours. I was reading about those, said they didn't have water bowels, either.

I thought, you know, on mine, can't they pump water aboard ship, but they must not be able to once, you know, they're set or something.

CB: Where would the water ballast be stored?

CA: Well, you got water ballast tanks and you got oil tanks, compartments below deck in the ship. And the water ballast was when you're low

on fuel, they'd take on more water so the ship will float right.

CB: Well, were there sharks? Were you able to see sharks?

CA: We saw sharks all the time, they followed the ship. Sharks and porpoises, both eat the garbage.

CB: What did you do next?

CA: I was talking about Saipan. We chased the fleets, but it was most all air battles. We'd get close to the Japanese fleet, hundred,

hundred and fifty miles, and planes would take off and they were aerial battles. They weren't ship to ship except where we'd get in

five mile range, our guns would reach file miles, they were five inch guns. Shell about that long, and course, five inches around. And

that was our battle, using that and depth charges, and we had anti-aircraft guns. I manned that on one of the ships.

CB: Oh, did you?

CA: Yes, uh-huh. We had what we call forty millimeters, they were shells for shooting down planes.

CB: Is that what you shot?

CA: Yeah. And I fired the twenty millimeters which is a lot smaller, and that's when planes get too close to you, you use the twenty

millimeters. Forty millimeters was the planes way up in the sky, dive bombers we'd say that, you know, just came over and dropped bombs.

Our main weapon was the five inch shells and that's what we shot at fleets out of our vision. Our shells would go over the horizon.

CB: A five inch shell?

CA: Five inch shell.

CB: That's big, isn't it?

CA: Uh-huh. Five inch round and about twenty-four, twenty-eight inches long because we could shoot lots of those things. In battles, the

brass casings, big shells are just like a rifle shell with brass. Our decks would be full of those things making all kind of noise rolling

across the decks.

JW: When we were growing up, you'd see a lot of those shells that were turned into lamps or little short tables.

CA: Yeah. It was so hurtful to see. You know how brass was so scarce in this country and here we had to get them off our decks because you

couldn't walk for them.

JW: Just threw them overboard?

CA: Just threw them overboard, yeah. We didn't have room for them anywhere else. Destroyer's an awful crowded ship. It's three hundred

feet long and you got three hundred and thirty sailors, so that's a foot a sailor.

CB: That's not much room.

CA: All the sleeping on the ship is below deck. I got my baptism, they put me in a swinging hammock right above the screws of the ship. And God,

they were noisy. You couldn't hear anything with those screws grinding, one on each side of you, and you was trying to sleep right between them.

But you know, destroyers was the preferred ship for sailors because everybody knew everybody aboard them, and they're fast. They'd get away fast

where you don't want to be or get to somewhere where they wanted to be.

CB: I hadn't heard that.

CA: It was a favorite ship of sailors. They all wanted on the destroyer. I was lucky to get on three of them. And we never lost but one man.

CB: Is that right?

CA: And he disappeared overboard during that typhoon. Never lost but one man on the crews and we went through hell at times.

CB: That's impressive. What else can you tell us about after you left this duty?

CA: After I left?

CB: The Pacific? Did you go then back to the Atlantic?

CA: No, I came home. That was when I had to have rest and relaxation, me and Halsey. That was the only two that left that day. He flew off the

plane, I had to ride that baby flat-top for thirty days to get home. Baby flat-tops were nothing but liberty ship hulls and they put a flight

deck on top of them. And they were used primarily to transport planes out, new planes out, wrecks that were salvageable, we'd carry them back

on these baby flat-tops. But most of my fighting was aerial fighting and trying to ward off planes, and all that took place in the Pacific.

It was just submarine duty in the Atlantic.

CB: That's interesting.

CA: Well, it's hard for me to bring up what went on because as I say, we tried for years to forget it. And then I've read more in the last

two weeks trying to catch up on the knowledge that we had. But as I say, as I told you, we found out after being associated with good friends

back here, why, we fought in the same battles together, we didn't even know we was in the Navy, but it was just trying to forget.

Mrs. Alley: After he came back to the States, after this rest and recreation, he was sent to Memphis Air Station.

CB: Oh, at Millington?

CA: Yeah, I was in Millington for seven or eight months and the war was over, ended up in Millington. That was good duty because I came home,

Johnnie and I lived in an apartment in Memphis and it was great.

CB: When were you released?

CA: Released October 23rd, 1945.

CB: And did you come back, did you come to Fort Smith then?

CA: Yes, Johnnie lived in Fort Smith during the war. When I went in, I lived in Benton, but her folks lived here and so she stayed with

them during the war.

CB: Did you go back into furniture right away?

CA: Uh-huh, yeah. A friend in Benton, I went back the Monday after I got home on the weekend, I think, went back to work. Why the hell didn't

you take thirty days off.

CB: You needed the money, I suspect.

CA: I expect that's right. They paid sixty dollars a month, the Navy did. And I think I made eighty-five dollars when I went to work at the

furniture plant.

CB: Where'd you go to work?

Mrs. Alley: He went back to work in the same factory.

CA: I was, I was with that factory, it was a big factory.

CB: Who'd you start to work for in Fort Smith when you moved up here?

CA: Up here? Flanders, Don Flanders.

CB: When was that?

Mrs. Alley: '58 or '59.

CA: Yeah. Don wanted me to come work with him and his daddy gave him fifty thousand dollars, and I didn't have five dollars. And he

told me I could buy later, the amount he did; but I never did. I bought some, he gave me a lot of stock. Don was in the Navy, too.

CB: Well, did you always work for Flanders then?

CA: Well, always, until my son and I put in a furniture factory in Van Buren and one in here, in Fort Smith. Yeah, we still own the

factory building down on the river.

CB: When did you retire?

CA: Two years ago December 31st, end of the year. We owned our own factory then and we closed it out. At that time, the Japanese had

eaten us up, we couldn't compete any longer. That's typical of the furniture industry in America now, the Orientals have it all 3

CB: Chinese or Japanese.

CA: All Orientals. There's just very few factories left in this country.

JW: Well, at one time, Fort Smith was number two behind Grand Rapids, Michigan.

CA: That's right, yeah. High Point, North Carolina; Fort Smith and Grand Rapids, was the last big furniture. Well, Virginia had some,

too; but none left anymore. It's a shame.

CB: We're interested in the history of the furniture manufacturing in Fort Smith. Has anybody written that history, do you know?

CA: I've got some history on it.

CB: Do you have?

CA: Yeah. I'd be glad to furnish it. Somebody wrote a history on it. Hold on just a minute. That's a history. You're welcome to take it

and copy it, if you want it.

CB: Does Chuck have a copy of this? I'll borrow it and make a copy. I'll let him know that.

Mrs. Alley: Is that the name, Charles, that Gene Radley and Jack told you about? Raney?

CA: Uh-huh.

CB: This is nice.

CA: Yeah, it's the early history of the furniture industry.

CB: Oh, yeah. 1892, incorporated Fort Smith Chair. Henry Hoover. Oh, great. I'm so glad you have this.

CA: I just have that one copy.

CB: I'll be careful with it and give it back to you. Who all was in business with you, in the furniture business?

CA: Well, there's Don and I, and my son and I.

CB: Who were some of your buddies down there?

CA: Oh, I knew Jim Ward. I knew Oglesvies, Grovers, I knew all of them. We were a pretty close-knit bunch. Yeah, we were here

when furniture was real active, we were active, too.

CB: Biggest industry in town.

CA: Started in Van Buren and ended up over here.

JW: I was always told that the decline of the Fort Smith industry started when Dixie Cup opened, because Dixie Cup paid so much more.

CA: That's correct.

JW: Than the furniture factories could.

CA: Yeah. I remember when I was building a plant in Van Buren, two railroad men were there. And one of them said, say, that's the lowest

paying wages you can find anywhere, the furniture factory 4

CB: Well, we still have Riverside.

CA: Well, Riverside, my son told me last week that they're closing.

CB: I didn't know that.

Mrs. Alley: That may be a rumor.

CA: Yeah. He said it was rumor, I wouldn't doubt it because they was making hardly nothing. They were importing. That's all except some

upholstery plants, except Riverside. And say there business is probably ninety-five percent imports. Just make a few little items, small

quantity. See Flanders and Riverside had the same sales forces, so we worked real close with Riverside. And then Riverside bought Flanders.

JW: Flanders is still operating, isn't it?

CA: It's in metal chairs, though, aluminum chairs. And I think that's about all they make, yeah. I don't know, probably seven or eight

thousand furniture workers here at one time. Biggest payroll here in Fort Smith.

JW: I lived at Edna Baughman's house the last ten years of her life, and it was kind of spooky. You know, her father was the father of

the furniture industry, and he died I believe it was 1924, and he evidently had heart trouble the last year or two of his life. Anyway,

what I'm getting to is they had kept the room that he died in, in Mrs. Baughman's house, the way it was when he died. They didn't make

a big deal about it, but it was at the back of the house, it was a room they had put a bathtub in. Evidently he had trouble getting to

the original bathroom. Anyway, it was just pretty strange in the late '70s and early '80s to know that that had just quietly been kept

like that since 1924. I don't know-- I never, course, didn't know him, but I sort of feel like I knew him because of all of his things

that were still sitting there.

Mrs. Alley: Did she live on the corner of Dodson and something?

JW: No, this is on North 16th and E.

CB: Oh, is that your son?

CA: This is our son, Gary. No, not Gary, Gary's gone. This is Calvin.

CB: We're recording World War II experiences or have been.

CA: You're not still taking pictures, are you?

JW: Yeah, I was.

CA: I think you got enough. No, this is an Arkansas project, I guess, isn't it? Who's paying for it?

CB: Well, the Fort Smith Historical Society bought the camera. And Joe and I are pretty well buying tapes. We're open wide for donations.

CA: It's a project of what remains of the old veterans

CB: We've interviewed I guess thirty or more veterans, mostly in the last two months.

Mrs. Alley: Was it Army, Navy or pretty well split?

CB: Well, it's pretty well split. And we've had, what, three Waves we've interviewed, one woman Marine. And it's been a very

interesting project, very interesting, lots of interesting photographs. Probably most of the people we've interviewed, though,

had been in the war in the Pacific. We've got several more people to interview this week

USS Carmick

USS Charles J Badger

USS Twining

USS Nehenta Bay

|

|

|

|