Vern Harold Ussery

1923 - 2006

Vern Harold Ussery was born March 12, 1923 in Wood Long, Wright Co., Mo. to

Peter McKinley & Hattie Ada Tankersley Ussery. By 1935 the Ussery family

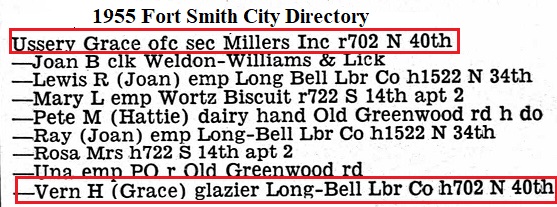

was living in Fort Smith, Sebastian Co., Ar. On Aug 5, 1945 Vern married

Grace L. Carter at Fort Smith, Ar.

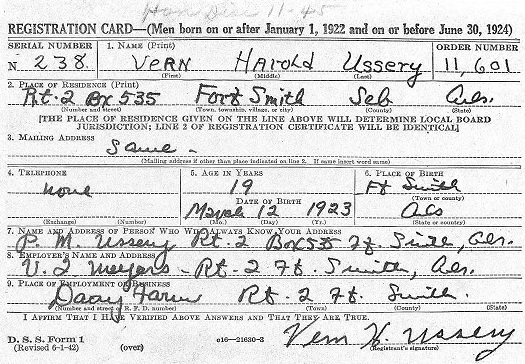

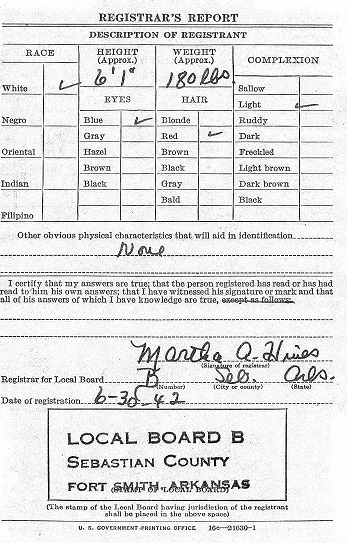

On June 30, 1942 Vern registered for the military draft at Fort Smith,

Arkansas. He enlisted in the US Army Air Force Jan 6, 1943. He served as

the flight engineer on bombing flights. His discharge date was November 7. 1945.

The rest of TSgt Vern Howard Ussery's story is told by him below his

obituary along with missing reports of the crew he served with.

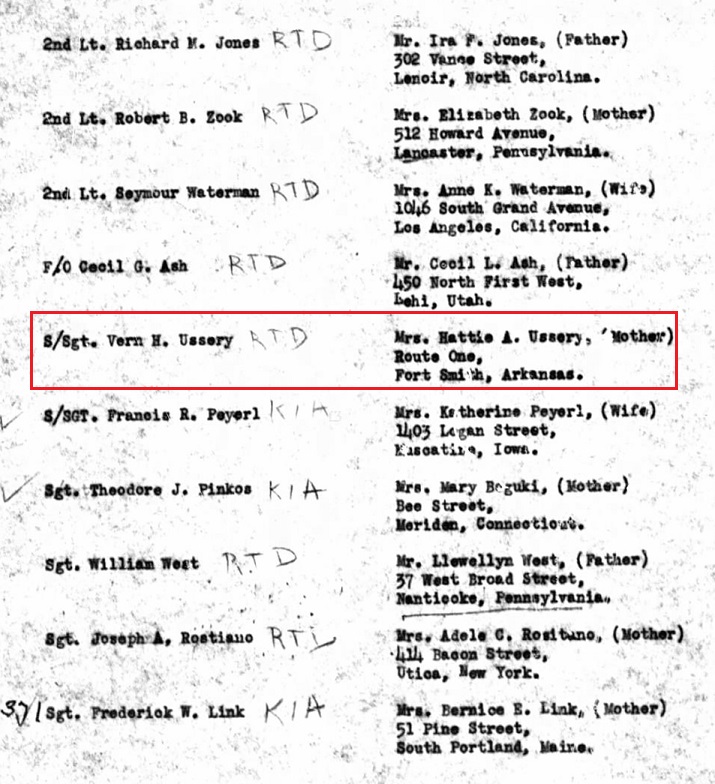

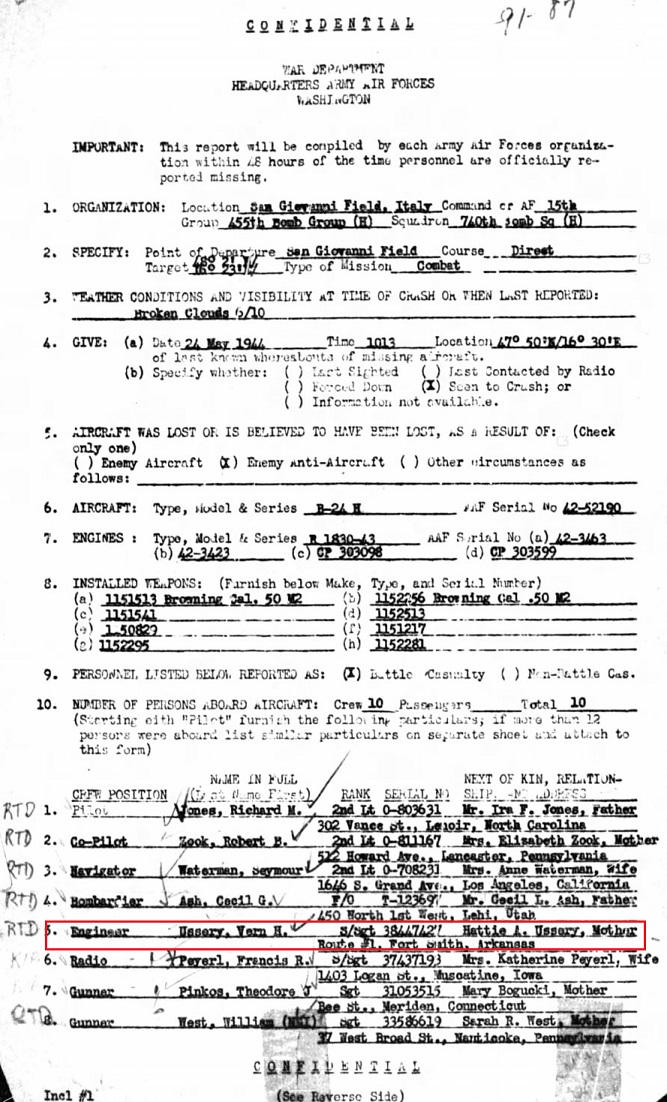

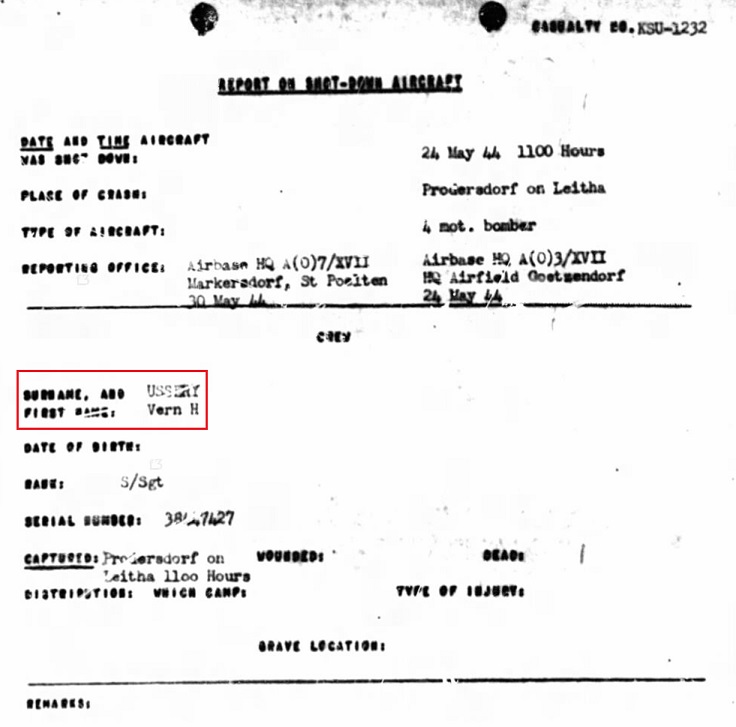

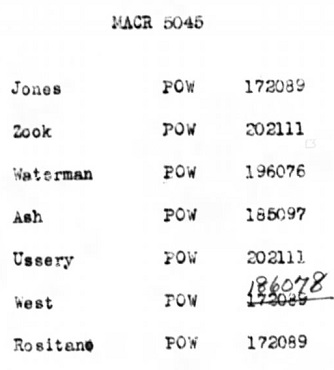

World War II Prisoners of War Data File, 12/7/1941 - 11/19/1946

| SERIAL NUMBER |

38447427 |

| NAME |

USSERY VERN H |

| GRADE |

Staff Sergeant |

| SERVICE CODE |

Army |

| ARM or SERVICE |

Air Corps |

| DATE REPORT |

May 24, 1944 |

| STATE OF RESIDENCE |

Arkansas |

| TYPE OF ORGANIZATION |

Heavy Bomber |

| AREA |

European Theatre: Austria |

| LATEST REPORT DATE |

Feb 18, 1946 |

| LATEST REPORT DATE |

July 21, 1945 |

| SOURCE OF REPORT |

Individual has been reported through sources considered official. |

| STATUS |

Returned to Military Control, Liberated or Repatriated |

| DETAINING POWER |

Germany |

| CAMP |

Stalag Luft 4 Gross-Tychow (formerly Heydekrug) Pomerania, Prussia (moved to Wobbelin Bei Ludwigslust) (To Usedom Bei Savenmunde) 54-16 |

from Find A Grave

Vern H. Ussery, 83, of Fort Smith passed away Monday, March 27, 2006, in Fort Smith. He was retired from the Woodworkers America as International Labor union representative. He was an Air Force veteran where he was a POW of World War II and member of the First United Methodist Church Gleaners Sunday school class. He was a member of the American Legion, DAV and the Purple Heart. He was a 32nd degree Mason, a member of the Belle Pointe Lodge No. 20, Amrita Grotto, the Fort Smith Shrine Club, UCT and the 455th Group Association Inc.

Funeral service will be held 10 a.m. today at Roebuck Chapel with interment to follow at the U.S. National Cemetery under the direction of Edwards Funeral Home.

He is survived by his wife, Grace Ussery of the home; sisters, Faye Wier of Fort Smith and Alline Greenfield and husband Wallace of Norwood, Mo.; brother, Ray Ussery and wife Joan of Fort Smith; and several nieces and nephews.

Honorary pallbearers will be the Gleaners Sunday school class and the P.O.W. Club members.

World War II Veterans History Project

The Fort Smith Historical Society

http://fortsmithhistory.org/index.

MR. USSERY: Good morning.

I'll try to not take too long. I was a member of the 455th Bomb Group, and I brought a copy of the history of that bomb Group.

It was in the 15th Air Force, the 304th wing, it was in Italy. It was unique in quite a few different ways and I'll give you a

brief description of it.

Our officers of the squadron and the groups, the principal officers, were people that had completed their bombing missions,

their tour of duty in the 8th Air Force, B-24s. Some of them had completed more thana tour of duty. And some of them were

officers that flew in the North African Campaign in B-24s in late '42 and through '43. And we had extra officers. They were,

to a man, either Lieutenant Colonels, or Bird Colonels, and they would alternate as leaders of the flights, or in

The capacity of pilots, co-pilots, bombardiers and navigators. So we experienced leadership. Our Group commander, when it started

out, was a Colonel Cool. And after the first month, he was promoted to a brigadier general. We were one of the few groups that

had a general as a commanding officer. And the navigator, the lead navigator of our group, was called back to Washington just

before the end of the war and was presented the Legion of Merit Award which included the 15th and the 8th. Our group won over

sixty percent of the awards which were made monthly for bombing accuracy in the entire 15th Air Force. And it wasn't only to

this one man, it was to our superb pilots and the navigation; but it's something that everybody that was a member of the 455th

was certainly proud of. Our percentage within a thousand yards of the center of the target was something like 78 percent through

the entire life of the 15th Air Force. Now, our logo was given to us, the name pinned on us by the other groups around us, we were

called the Vulgar Vultures. Now, why, I don't know; but it shows a buzzard riding a bomb. And that's what they called us, the Vulgar

Vultures.

We have reunions every two years and have ever since the war. And some of those Colonels that come from the 8th Air Force in the North

African Campaign put this history together. It contains the date, the destination of the mission, and a brief summary of every mission

that we flew. And course some of us didn't make all those missing, like myself; They got taken out of it.

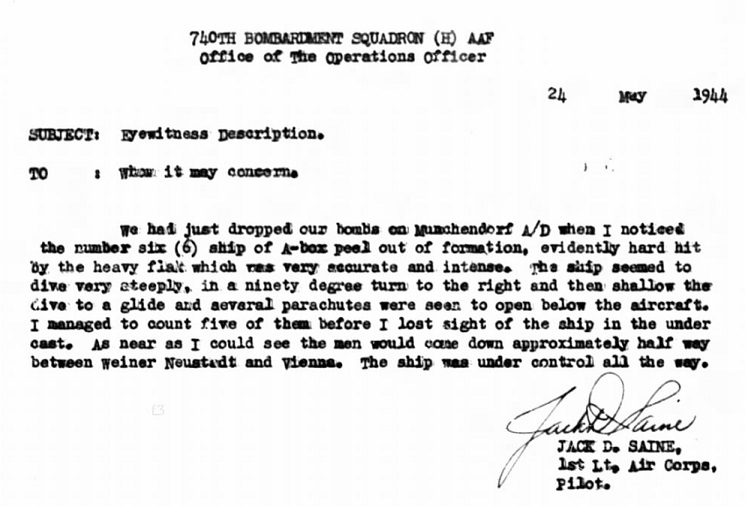

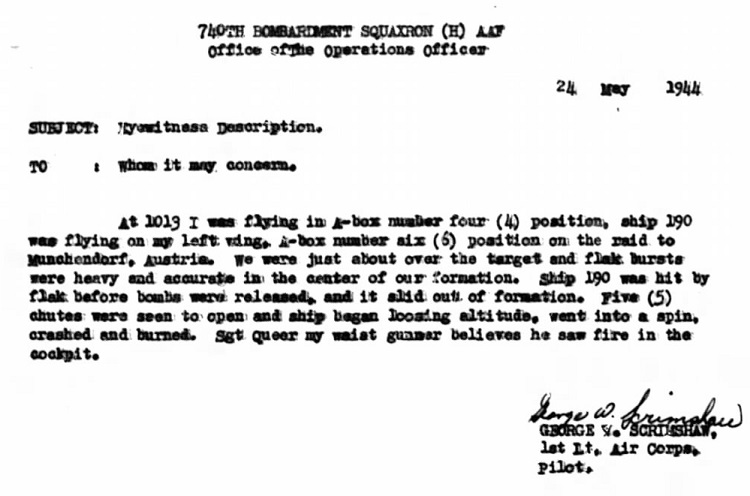

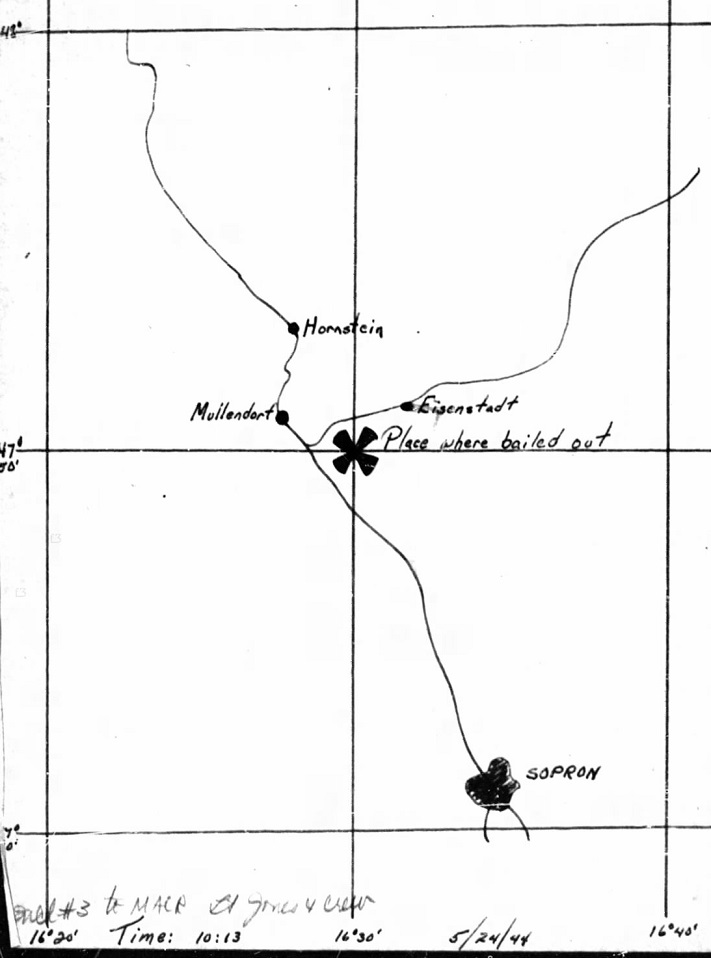

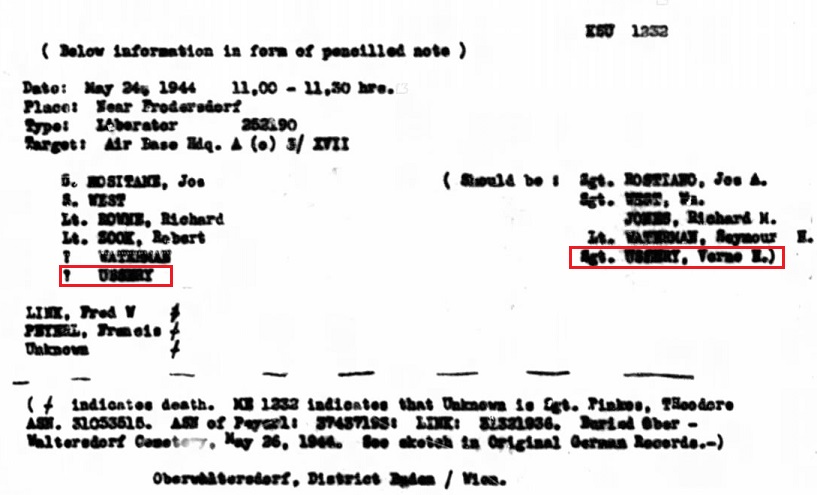

But to start with the horror story part of it, May 24th, 1944, our target was Wiener Neustadt. And Weiner Neustradt was, I would say,

comparable to Ploesti for flak and being known as a rough target, it was a booger. We were flying, my crew, another crew's airplane;

we didn't have our own that day. And we had a buckshee co-pilot which gave us bad luck. Anytime that you had a buckshee or an extra

crewman from somebody else's crew mixed in with your crew, it was a omen, at least to us, of bad luck, we just felt that. But we had

a co-pilot assigned as 1st Pilot, he was a 1st Lieutenant co-pilot. His name was Jones and he was assigned as our 1st pilot that day.

And ordered that he had to fly some missions as 1st pilot in order to be promoted to captain before he rotated back to the states, and

he had in 47 missions. This particular mission would have been counted as two. A long mission gave us credit for two sorties or two

missions. So if he'd have completed this one, he'd had 49. and we record 50 to come home. But on the way to the target, the plane

kept veering to the right suddenly from time to time. And finally, he pulled to the right, out of the formation, dropped back and

fell behind the main group. And the problem was that the right landing gear on that B-24 that we were flying that day, the name

of it was Bucket of Bolts, the right landing gear would just inadvertently fall down from time to time out of position into a down

position and that would jerk the plane. And we had to get it out of the formation and get it behind to keep from jerking into another

plane. Well, that put us in a position of over the target where they dumped out the chaff or the little tin foil, that put us in a

position of being low in and to the rear. And the guys up front would dump the chaff out and it was floating all around us, and it

attracted the radar fire, and got it.

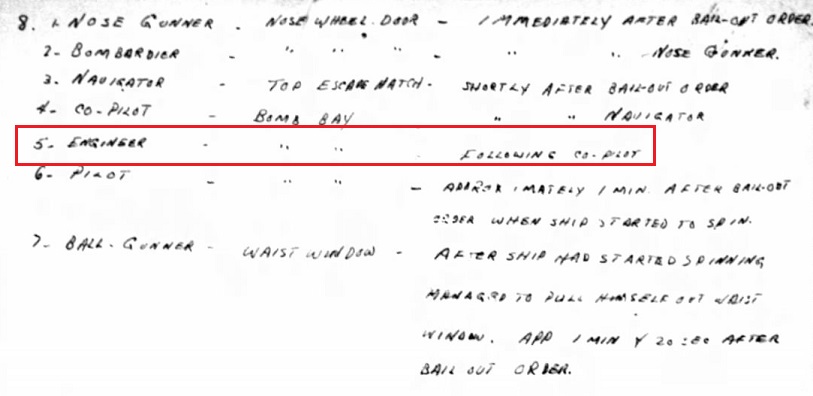

I want to say couple of words about my position. I was engineer, top turret gunner. I sat in the top turret and I had a Plexiglas dome

around my shoulders and my head, had two 50 caliber machines guns, and I sat up in that dome. And from that position, you can look forward

either side, up or down and look back. And it was a sight to see then you were like in the center of the bomber's tree on a major effort

target. As far as the eye could see, you couldn't see nothing but bombers, forward and back. And it was a good position to me because

the tail gunner, all he could do is look back, he didn't know whether people were still ahead of him or not. And the nose gunner, all

he could do is look ahead, he couldn't see back. But in my position, I had a view of all of it, I could see the whole works.

But anyway, on May the 24th, coming into the target, we were flying high for a 24, at about twenty-six thousand feet. And we got hit

in the nose and we got hit between the flight deck and the right in-board engine, right near the radio operator's table, who was, the

position that day was occupied by the navigator. And that shell bursted my turret, the Plexiglas, it just went into a million pieces.

And I had on an old steel infantry helmet that we work over the target areas. And that doggone thing, I didn't have a liner, and over

the target area, that old helmet would come plumb down to your nose, and had to keep pushing it up to see. But you didn't really like

to look at all that stuff bursting around you. And I mean to tell you, it busted around you. And when that Plexiglas busted, that old

helmet went bouncing down the top of that airplane. It came off my head and bounced down the top of the airplane and off the rear end.

Well, then there was a fire started on the flight deck. The shell bursted the hydraulic lines and the oxygen lines, and we had a

heck of a fire going in that flight deck. Well, I got out of my position. The pilot went to hollering over the intercom "Bail Out,

Bail Out, Bail Out", and he pushed the bell that warned the bail out. And I got down out of my position and there was a door at the

back of the flight deck. The door was three quarter inch birch plywood, it come down on top of a door that fit in the bottom of

the flight deck, and this top door had to be raised to raise the lower door. You had to push it up to raise the lower door.

And some of them was red, and some of them green and yellow, different colors for different emergency things. And that made some

fireworks sure enough. But the fact that my turret bursted, the flame and the smoke was sucking out the top of that hole, it was

going right on out. But anyway, I kindly backed off, away from that door that was stuck, and something told me to lay on my back

and kick it and I did. And I was able to burst that plywood and get that door up and raise the other door. Well, my pant legs,

by that time, of by flying suit, was on fire. And the pilot went by me out onto the catwalk into the bomb bay. And when I saw

him couple years ago in Colorado Springs, he told me that he was sure glad to see me when we got on the ground because the last

time he saw me, he said, "Your britches was on fire." But he went home. But anyway, I knew I had to put them britches out before

I jumped out of that thing. And I did, I got them out and I bailed out.

And we were pretty high, some of the boys didn't make it.

I opened my chute immediately, which was a mistake. And as I was floating down, well, there was one other thing. Before I left the

catwalk, I had a cap with a long bill on it and I had my name stenciled on it. And I went back in that flight deck and got that thing.

Now, why, I don't know; But I felt like I had to have that cap. But when I putted my parachute, the ripcord, and I don't that pretty

quick, it was a tremendous jerk. My feet went up and actually hit me in the back of the head. And my flying boots both come off.

They was zipped up almost to my knees, but they come off, they went a way out yonder. And at that same time, I lost my cap. And

this old cap filled with air and it was spinning around and around and around, right up there with me. And I kept trying to get it

and the air come out of it and it just collapsed and the old cap went off, I lost it. But wasn't but just two or three minutes that

I saw a group of B-24s that was flying lower than we were, coming by. And one of the planes dropped out of position a little bit and

come over toward where I was. And it appeared that the co-pilot, it appeared to me that he had a camera, they come pretty close.

But anyway, the crew of that plane waved at me, and they give me that, but I went on to the ground.

The parachute ride was extremely quiet, you couldn't hear nothing, it was just deathly quiet. Got down pretty close to the ground

and you could hear, it sounded like compressed air, just a little psht, you, like that, and then a little pop. And the pop was

above me, and every time I could hear that, I looked up and there would be a little black stop in my parachute. Well, I knew

then that I was getting shot at. So I stated jerking on those lines and I got that thing swinging pretty good and I made it on

to the ground and come down in an area where they were doing truck patch work. And there was an old lady just right there in

front of me as I come down. And she looked up and saw me, and she crawled the length of this room, crawling on here hands and

knees before she could ever slow down enough to run, she took off. I hit the ground and rolled over a few times and got my

parachute collapsed. And there was people working their gardens and stuff around there and they came running up there.

A man wanted to know if English or Americana, English or Americana, and I told him I was American. He shook hands. And pretty

quick, there was an youmg man, and I took it to be his son, about twelve years old, come running up there. And he had a spading

fork and he had that old spading fork drawed back and he was just screaming and hollering and carrying on something terrible.

And I thought he was going to try to hit me with that spading fork. And I'd already taken my harness off, my parachute harness,

I had on a chest chute, and I rolled that up. And it had great big old buckles on it, as you guys that bailed out know that those

parachute buckles are heavy. And I rolled that thing up and he come at me with that fork and I come down over his ears with that

harness of that parachute and it backed him off. But I wasn't going to stand there and let him gouge me. And there was several

other people gathering around.

I saw that German helmet coming on a bicycle, down a little old trail there, here he come.

And he rolled up there within about a hundred feet of me and he parked his bicycle, throwed it down. He had a rifle and he

brought that thing up and he was pointing it at me, and he was just squalling and hollering. I couldn't speak German, but

this fellow that could speak English that was in the crowd there, he said, "He wants you to put your hands up." Well, I complied

pretty quick, and he wanted to search me. And that old long squirrel gun he had was just swinging in a circle right in my face

and that barrel looked like a stovepipe. And he would reach up there and he was trying to search me, and he was hollering "pistoal,

pistola." And I knew that he was looking for a pistol because most all airmen were issued a .45. Now, we didn't wear ours,

our crew didn't. We figured it's just get us in trouble as deep into Germany and the occupied countries that we went and we

didn't wear ours. But he knew that we normally had those, and he'd reach up there and try to search me and what not, and he

jumped back.

Finally he got me searched and he told me to pick up my parachute, and this other guy there told me what he said. And my left

foot was hurting me real, real bad, I'd been hit in the left leg, and through the bottom of my flying boot and boot. And he

headed me off down this road, following me. And one of the other guys got his bicycle and was pushing it along behind us.

We went about a mile, come to a little old village, and you never seen the lick of women in your life come out there. And

every one of them had a knife or a pair of scissors, mot of them scissors, and it kingly bothered me because they kept coming.

And what they wanted was my parachute, and they cut that things to shreds. I was kind of glad they did because it was pretty

heavy dragging. And they got every bit of it and kindly fumbled around there looking for more.

And as I went on through that village and a next one, they took me up on a hill where there was a radar, German radar operation.

But in the meantime, before I got to that first village, sitting under some bushes, two German soldiers got up and followed

along behind. And they wasn't over a hundred and fifty yards from where I hit the ground, but they were hid under those bushes.

And I kind of figured that they were the two that were shotting at me up there in the parachute, I don't know. But anyway, my

foot was injured and my left leg. And they took me up to this radar installation. And they had some holes dug up there about

that big a square and they were pretty deep. And they picked me up by the arms and put me down in one of those holed with my

hands down beside me. Well, I was crammed in there, there was no way I could get out of that thing, absolutely no way. And

this German that was in charge, he blabs off at me and told me the usual that I'd be home in a few weeks and the war would be

over, they were going to win it and all this kind of stuff. And then he hollered at some of those other Germans there and he

lined five of them up with rifles right there by me. And he give them the command to about-face, marched them out maybe half

the length of this room and halted them, turned them around, give them some other orders, and they come up with them rifles

right at me. And he give them another order, and boy, they worked that old bolt. And I thought, well, this is it. And then

he said something else to them and they dropped their rifles and he come back up there where I was at, just dying laughing.

God, he'd had him a joke because he knew he'd scared me half to death. And it was funny, it was kind of funny to me, too.

Anyway, a group of B-17s come over the same target, way high and a way back up there, and they got real busy running those

radar things and what have you. And I was out in that hole, they didn't have to worry about me, they had me. And they shot

one of the B-17s down. And that thing exploded and there was four pieces of it up there, way, way high. And all four pieces

was just burning like crazy up there. And I kept looking for parachutes and I never did see any. And he came back over where

I was and he told me, again, that in a few days that the air force would be kaput. Showed me that one, it was still falling up

there. And I made a mistake, I told him that we'd have a hundred back to replace that one, and that made him mad, and he started

kicking me. And there wasn't nothing but my head sticking out of that hole for him to kick, and I lost three or four teeth.

I learned to keep my mouth shut right there.

They took me then in the afternoon, marched me down to another village and I run

across my pilot and my navigator, they had them there. And long up late afternoon, the commander there at that little house

where they had their headquarters, asked me if I was hungry, and I told him I was. And they didn't ask my pilot or navigator,

they just asked me. I told him, yeah, I was hungry, I was. I hadn't had anything since three o'clock that morning. And he

bellowed out there to a German private. That dude went out in the garden there and he pulled some stuff that looked like onions,

they called it leeks, had wads of dirt on them roots like dirt-daubers' nest. He brought that in and dumped it in a pan with

water in it and he proceeded to cook me a little soup, dirt and all. And you know, he give me a spoon and I kindly let the dirt

settle, and I took a few bites of it. My pilot and navigator was setting there looking hungry.

Later on that evening, they brought a

about like a Volkswagen down, two German soldiers in it in Luftwaffe uniforms. And they got the three of us

and loaded us in the backseat of that little old car, I mean they jammed up in there to get in and down the road we went. And I'd

never seen a kilometer speedometer before, measured in kilometers. That kilometer's not as long as a mile, not nearly. And here

these dudes go with us in that backseat down that cobblestone road and that thing was registering seventy and seventy-five miles an

hour, I thought. It wasn't running over about forty-five, I don't guess; but god, I thought we were a flying. And they took up to

an air base up near the target that we were bombing which was Wiener Neustadt, and they put us in a room at the end of a long barracks,

German barracks and they had some tow sacks there on the floor, filled with straw. And they left a guard in the hall, locked the door

and barred it, and there was a little window way up high in one end, we were in the end room with a window that went outside. And we

weren't in there very long until in come a potato through that open hole, maybe a little old black piece of bread or two, and eggs,

boiled eggs, pieces of old fat sow belly and carrots and turnips. And you had to stay out of the way because you didn't know when

that was coming through, and they'd throw it in there. And come to find out, the pilot told them he had to go to the restroom, so

they took him outside. And it was these Russian Prisoners of War that had the run of the air base that were throwing that food in

to us. And lord, we couldn't begin to eat all they threw in there and we begin to hide it under those old sacks. They took us out

of there the next afternoon and we had enough in there to eat for a week or two.

And they took us out of there the next afternoon and we had enough in there to eat for a week or two. And they took us into Vienna,

put us on a train and was going to send us, they said, to Frankfurt. All the airmen in Europe went to Frankfurt for interrogation.

Well, the British bombed the railroads out at St. Polten, Austria, and they took us off in ab out an hour and we hadn't traveled far.

And it was black as night and they marched us through the street there to a jail in St. Polten. They put me in a room tat was

about maybe six foot wide or eight. Went into that room and they had a rock ledge about as big as this table built up, straw on

it for your bed. Had a real dim little bulb way up high in that room, ceiling was tall. And I'd lay down in that straw and, boy,

that's where the lice got me, and the fleas, anything that'd bite, and I had a miserable night. And you could lay there and you

could hear the darn rats coming, playing around in that straw in that place. And they kept us there until the next day and then

they took us by truck out to an air base at St. Polten.

We stayed there a few days and then we went on to Frankfurt, went through interrogation. And the usual, the fellow that interrogated,

most all, he told me and a lot of the others that I've talked to, that if you didn't tell them where you was out of and this and that

and what not and what have you, you'd be turned over to the Gestapo and shot, and so on and so forth. And I'd give them my name, rank

and serial number and that's all I ever give them. And you know, he turned me loose out of that room, guards come and got me, took

me down to the end of the hall and stripped me off and searched me again and put me out in a stockade.

Two or three days after that, we went to a fort Wetzlar, Germany. And they kept us around there about a week and then we loaded onto

a box car, and that was the 6th day of June. And the reason I know, when we loaded into that little old box car, one of the German

guards told me that we'd be going home in just a few weeks, that the Americans had landed that day in France, D-Day. And that soon

as they beat them off and whipped them, well, the war would be over. Well, they loaded us in the box car and we was on that thing

eight days and nine nights. They opened it one time during that trip. They give us a couple of buckets of water in there and they

had fifty-two of un in that little old thing, I believe. And we had to stand up and take turns with the guys laying down that was

getting sleep or maybe some of us just slept standing up. And we finally got to the prison camp which was Stalag Luft 4.

When we got there, will, course we were unloaded and they double-timed us from the unloading place to the camp, which ws, I don't know,

two, three miles, something like that. Took us into the Vorlager and stripped us off and searched us again. And we'd had, during that

eight days or nine days, two blood sausages about that long, for fifty men or fifty-two. And they put in there few loaves of black

bread. I don't remember getting a bite of it. But anyway, when we got in the Vorlager where we were stripped.

That's the first occasion I had to meet I guess the most famous guard in Stalag Luft 4, and that was a fellow we all nicknamed and

called big stoop. Boy, he was a dandy, he was a giant of a man. And he was slapping the guys around and kicking them and beating

them and he was just horrible. And when they got through with us in the Vorlager, we kept thinking we were going to get something

to ear and they moved us inside the compound. And the compound, the barracks that I went in that was just starting to accept

prisoners there, and I went into barracks on, just inside the gate, room four. And nothing to eat that night yet. The next morning,

we got a pitcher, a great big old pitcher full of warm water, nothing else. And at noon, we got a little old potato about like that.

And at night, we got some kind of a pitcher for that room full of men full of some kind of old watery sout. And that was primarily

our diet that the Germans give us, except about once every seven or eight days, they'd make a bread ration issue and it finally

turned out to be seven loaves of bread for twenty-four men for eight days. And of a morning, sometimes we'd get what we called

ersatz coffee. It wasn't regular coffee, it was a fictitious type coffee. And out beds had six slats, it was about that side;

and our mattress was a tow sack filled with straw, which soon got all mashed down. And they would inspect from time to time to

see that we still had those six slats because the guys that dug tunnels and what not, would use those slats to shore up the tunnels.

But we had bed inspection from time to time. And that wasn't too easy to curl up on and sleep. And that old straw from the guy above

you dripping down on you in your eyes and your mouth all night. But our rations was just very meager, very meager.

We had no toilet tissue of any kind. We had no bathing facilities, no way to take a bath, no showers, nothing to bathe with.

We had an extra bucket and this old pitcher for the twenty-four men. And wehad a guy that'd go over to the kitchen and get our

ration for that room at

mealtime each time. And they had two headcounts a day, one of a morning and one of an evening. And they always lined them up by

fives, because that seemed to be the only way the Germans could count, was five, ten, twenty, like that. We stayed there until

February the 6th, 1945. That was when, early part of June, 1944, that I got there. And they continually took in other prisoners

and even another prison camp, Stalag Luft 6 moved in there. So the camp had a lot of men in it, several thousand. And we could

hear the Russian guns, artillery. But they marched us out and they told us that we'd be on the road about ten days. And they give

us, each one of us, a can of Bully Beef, ten about that long and about so big around, about like a coffee can that we use now, and

told us that that would be our ration. And we did have some Red Cross parcels, a little bit of stuff out of the And we marched out

on the 6th of February, deep snow, cold. And that night, I made the mistake of taking off my shoes. And the next morning, I couldn't

get them boogers on. Boy, I workecod on that to no end. Finally got them on without laces in them.

We stayed marching for eighty-eight days, up along the Baltic Sea. We did get into Falling Hostel Camp for three days, but we slept

in the mud and outside in the rain there. There was no tents, no rooms in any of the building or anything. And they marched up back

out of there, and we marched back across the Elbe River. And all this time there was guys with dysentery that turned to blood and

didn't make it. And it wasn't easy. And 2nd day of May along shortly after noon, they give us a rest that day, they didn't march

us that day. And shortly after noon, there was a German staff car with four German officers in it, had a convertible top and the

top was laid back, came down that little old road and he was a Mogulling. And right behind it was an American jeep, manned by

British soldiers, and they were firing at that dude. And I mean they were trying to work the tail end of that German staff car over.

They went right on by and, man, the minute they went by we took our Germ an guards' guns right there, we got them and we started

celebrating. In a few minutes, there was another British Weapons Carrier wagon come by. And they stopped and they told us to stay

there that night and there'd be trucks to get us the next morning. And within thirty or forty minutes after that, there was a Russian

Lieutenant showed up with a squad of men. And they butchered a couple of that old German's cows, but that meat up and built fires out

there. In fact, they bought one of their horse drawn field kitchens over there. And they cooked that meat and what not and what have

you for us. And out stomachs were shrunk so we couldn't eat. And they got kindly teed off because we couldn't. But the next day, we

waited around there until about eight o'clock. And the Russians posted guard that night around us to keep the Germans from throwing

grenades in there or what have you that they said they might do.

We pulled out afoot, heading back west. I was buddying with an old boy out of Tulare, California, that we called dumb John. And they

all nicknamed me as Big Red. Dumb John and I were going off down the road there going back west. And we saw a farmer, a German farmer

up there on a tractor on the side of the hill there not too far from the road. Old Dumb John said to me, said "that sure would beat

walking", and I said, "Yeah, I believe it would." And we proceeded to get that tractor. Dumb John whacked that dude, he wasn't

going to give it to us and Dumb John whacked him with a club upside of the head and took him off of that tractor. And we couldn't

go up any hill, it wouldn't pull it, and the guys would have to get off and walk. And we get to the top of a hill, we'd stop and

wait on them, they'd catch up and get back on the wagon and down the hill we'd go. And we made it to Lauenberg, made it I guess

fifty kilometers. We stole fuel from different farmyards along the way. And we made it in Lauenburg and we run into supply trucks.

And course, they tried to give us oranges and candy and stuff like that and you really couldn't eat. But anyway, we crossed the

river, the Elbe River, on a pontoon bridge. And that son-of-a-gun would just give it that all the way across it, It just made you

so sick that you wouldn't know which end was up. But there was one reason why we got so sick was we had some cigarettes these

truck drivers give us, and there was a Polack there that was a slave laborer, and he wanted to trade us a bottle of Schnapps.

And that bottle was not long for that cigarette, we traded. And that stuff didn't have a label on it and it was just clear as

water, but boy, you pull that lid off and you could smell it. And Old Dumb John and I drank that in the back of that truck on

that old wobbly bridge. I don't remember getting off that bridge. And few days later, two or three days, I woke up in a German

cavalry barracks, The next town which one time had been a German cavalry Barracks. It was occupied by the British. And I was

in the latrine and, God, I was sick and I was a mess. And Old Dumb John was just not very far from me. And when we come to, well,

the British said that they'd begin to wonder if we were every going to come to or not. And we smelled like the dickens. And they

took all our clothes off that we had, them old rags, them lice and what have you, and give us a complete British uniform. I mean we

looked just like British soldiers. And the British were going to fly us out of there.

We went to the airport on their trucks for four, five days and they kept flying their own British soldiers out and leaving us and the

Canadian there. So Dumb John and I decided what the heck, we'd hitchhike to the American line, we'd find it somewhere. And we got

on the back of the truck and when we went out on the highway, we just stepped off and give it the thumb, and the first truck come

along picked us up. And then we hitchhiked probably a hundred miles back across Europe there, maybe farther. And we finally come

to the Americans, and it was an infantry replacement outfit. They were in the German Barracks that was double-decker. And took us

upstairs and said they had roll call twice a day, but for us to stay upstairs and stay hid, so we did.

But a little shavetail Lieutenant come through couple days later and found us and he took us down to the headquarters. And some

Colonel down there, he chewed around on us for being up there in that barracks. But he didn't really know what to do with us,

and he told us to stay there and he'd be back. Well, when he left, we went out the window. And wasn't long until an MP check-station

got us, and they called for a squad car, and that squad car come and got us. And my beard was down to here and hadn't had a haircut

in a year. I guess I looked terrible. But they detailed this squad car to take us to an Air Base. And they took us to a P-47 outfit,

out there in Hamburg, Germany, somewhere in the aria of Hamburg.

Well, those guys were just nice as they could be. And they give

us a bed, boy, I mean a feather bed upstairs in a brick house which was headquarters and was just treating us royally. And Old Dumb

John would eat some of that chocolate candy bars. And a way in the night, he woke me up and they turned the lights off, and there

was a bathroom up there somewhere, but we couldn't find it and he'd done already passed needing it. We finally found that bathroom

but we really had to wait until the next morning and he finally got cleaned up. He needed a new uniform then. And they flew us that

day in a C-47 that went back to England each day, they took us to England, the P-47 outfit did. And we got to England and that

commander of that air base wouldn't have us. He said he had no facilities for us and didn't want us and he dispatched that place

back to France, to Camp Lucky Strike. And by that time, the lice had done gathered up in that new uniform real good. And we got

back to Lucky Strike and they turned us over to an outfit that was handling prisoners. And that evening, they took us down on a

creek bank and took those uniforms off of us and they sprayed our nude bodies with DDT. And they steamed those and had ovens for

those uniforms. And I brought my British uniform home with me, but they give me an American uniform.

I came back home on a

Liberty boat that had been around the north end of Sweden and Norway. And it had busted in the center and they'd welded plates

on it to hold the thing together. And they had pumps down in the belly of that thing. And as the water would run in, they'd

pump the water back out. It took us fifteen days to come from Le Havre, France, to New York, City. But when we got in New York

City, they kept us outside the port, got in there late on evening. And all night, there was some guys come out from the harbor

there and they put flags on this boat, from one end to the other on ropes, there was several streamers of flags. And next day

they'd run us up and down that doggone harbor and they had two big fireboats ahead of us and one behind us, shooting those streams

of water up in the air. And the other boats would blow three toots on their whistle, and our boat'd blow one. And they run us up

and down that harbor, that supposed to been a parade just about all day, and we wanting off. And finally, we got off and went to

Camp Kilmer.

19th day of June I got in Fort Smith on a troop train and come into the old station down there at Rogers, where the

Holiday Inn is now. And I heard some heels a clicking that sounded awful familiar to me. And I'd just got off of that passenger

car, and I heard those heels a clicking and looked up and here come Grace around the corner. She's found out someway or another

that I was coming in. She met me there at the station, 19th of June 1945. They put us on a bus and took us to Chaffee. Well, a

fellow by the name of Pendleton Woods and I come back on that same boat together. There wasn't no way that Pendleton and I were

going to stay in Chaffee, so we head off across the field, come out on the west end of Chaffee there, and climbed through the barbed

wire and come home. And meantime, Grace and her folks went out to Chaffee to get me. Well, I had to bum me a ride back to Chaffee

to go out there and get them.

That was just about the size of it. There's a lot of stuff happened on that March, lot of things happened. It was miserable,

it was bad, it was cold. Lot of Guys didn't make it, including my crew members. And one thing about it, they marched us west

out of that camp. It was a way over in the eastern part of Germany and every step I took was one more step toward home, and it

felt good.

Thank you.

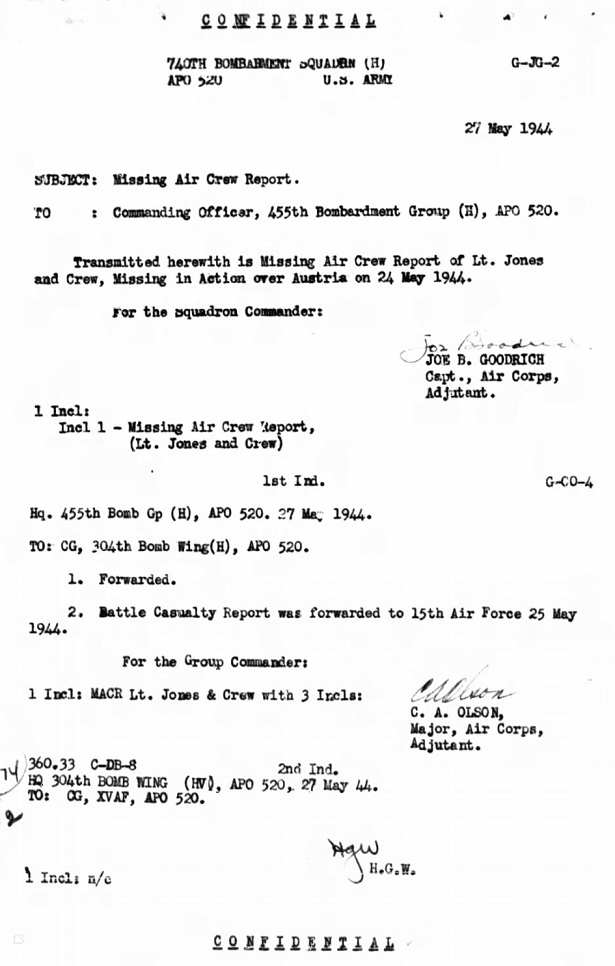

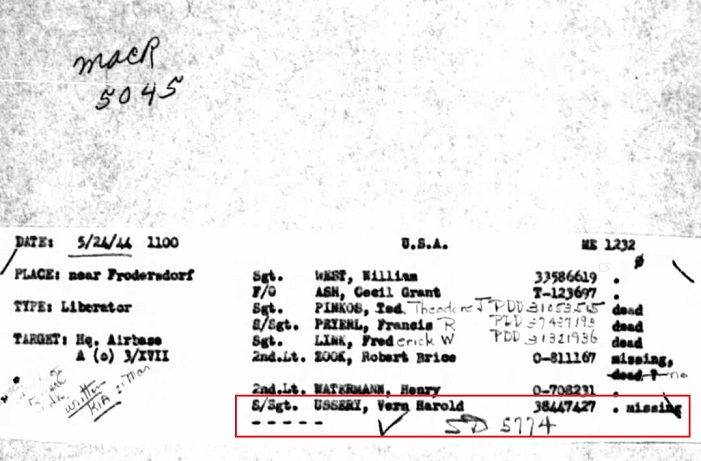

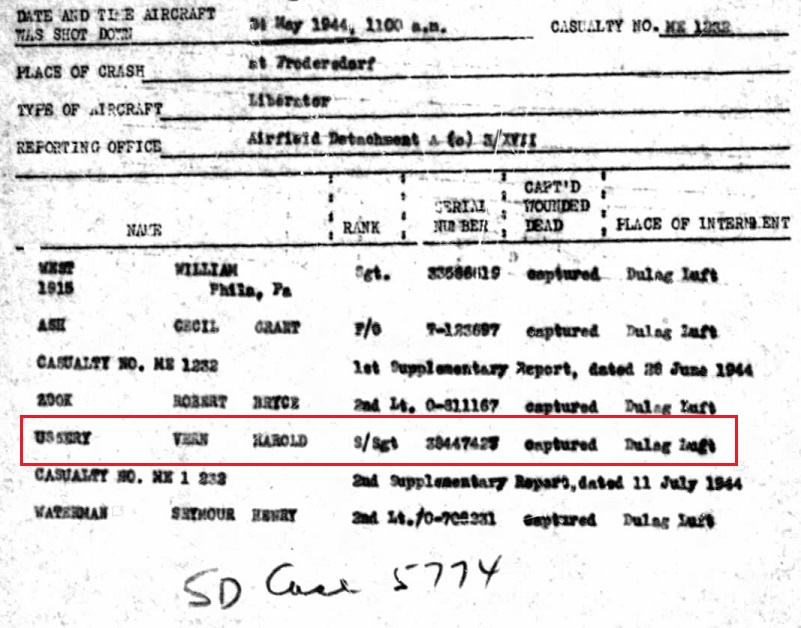

Missing Crew Reports

|

|

|

|