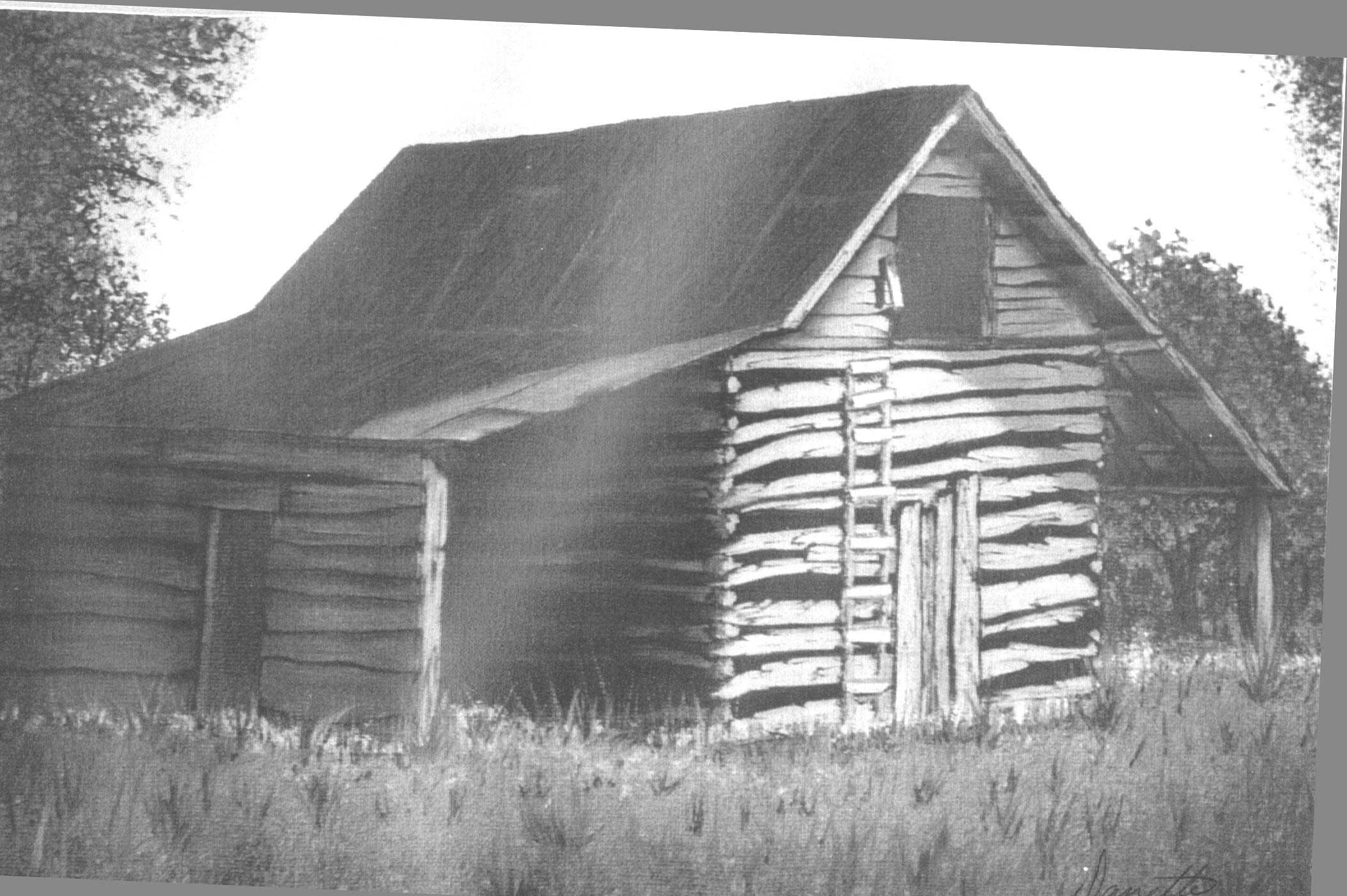

Jackson family barn at Clay

Colorful Past of Clay

A Farming Community With A Rich History

By HEBER TAYLOR

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 12, 1999

Clay, a farming community near Pangburn, is appropriately named, Searcy’s Carnelle Holcomb believes. She grew up there and says it has some of the reddest clay you can find. The community, which may have been named for southern statesman Henry Clay, lies east of Arkansas 16 on White County Road 305. It seems to have been settled in the mid-1800s by people moving west from Southern states.

Holcomb’s great-great-grandparents, J. J. and Winnie Howell, came from Kentucky in 1857. They received a land grant of 160 acres at Clay.

In 1858, their infant child died and was buried near their home. The grave would be the first of several hundred in what became known as the Howell Cemetery because the Howells donated almost nine acres of land for the community to bury its dead with theirs.

Another 1857 settler, Samuel Caruthers, received a 160-acre grant near the Howells. He gave 1.44 acres for a community school and playground and he became a trustee when a school was established.

Clay resident Glen Majors says that a log building erected for a church was also used for the school. "School, church, funerals and social activities were all in one place," he said.

In the 1870s, several Clay families came under the influence of a religious leader named Cobb, who had come from Tennessee. He thought of himself as the "walking preacher," and made a claim to divinity.

One Clay resident, a respected Civil War veteran who had come from Alabama, believed in Cobb’s divinity after the preacher told him about things that had happened to the veteran in Alabama. He didn’t know that his step-mother had earlier shared that information with Cobb.

The Cobb group formed a Utopian community and soon moved south of Searcy. Members became increasingly fanatical, and during a revival forced travelers to get out of their buggies or wagons to join them.

A Searcy bartender, said to be drunk, went to see what was going on. He was killed with an axe after he had hit the revival preacher (not Cobb) in the head with a fence picket. When word of the death reached the bartender’s brother, he formed a posse to go for revenge. In the confrontation, the Cobb people, believing they were divinely protected, told their enemies to shoot. Two were killed.

After some time in jail and in court, Cobb’s followers went back to Clay. Cobb had earlier been escorted to a ferry on the Little Red River and told to leave and not to come back.

Cloie Presley of Searcy has written about the followers after they returned to Clay: "They worked oxen, kept to themselves, had their church services, and made provisions for leaving. They went to Washington County, Mo., but it is not known if they joined Cobb there."

As the 20th century neared, a nice village was developing a mile or so from the school, church and cemetery. A post office was granted in 1883. In 1893, the school and church moved to separate locations close to the village.

The church, which was organized in 1850 after a brush arbor revival, had William Crutchfield as its preacher from 1890 to 1896. Glen Majors said that church records from 1903 to 1932 refer to the congregation as "the Baptist Church of Christ worshipping at the Mount Pleasant Clay Church." It is now the Mt. Pleasant Missionary Baptist Church.

The other church in Clay is the Pine View Church of Christ.

By 1900 or so, Clay seems to have had four stores, a post office, two cotton gins, a grist mill, a blacksmith shop, a Masonic Lodge, two livery stables, two sawmills and a doctor. There were enough houses close to the stores to make Clay a small town. Leon Van Patten of Searcy said his parents told him Clay was lively and well populated then.

A 1901 school program listed the names of 41 pupils who were studying at the Clay school between July 15 and September 16. In 1907, Clay got a second school, the Clay Graded School, which emphasized teacher training. Pupils in grades 1-5 were charged $1.50 for tuition. Tuition for grades 6-9 varied from$1.75 to $2.50

Boarding students paid about $8-9 a month to stay with families in Clay. Connie Yingling Patterson, a retired teacher living in Searcy, said two boys lived in her father’s store and two girls in the family’s home.

Leister Presley of Searcy said that his father, Luther Presley, came from west of Rose Bud to attend the school. Luther taught music there to pay for his tuition. He later became one of the state’s best-known writers of gospel songs. Two were "I’d Rather Have Jesus" and "When The Saints Go Marching In."

Leister Presley said that his parents met at the school. His mother told him that school officials closely checked on student behavior. "She said that my father left a note for her by a path," Leister said. "The superintendent’s dog found it and delivered it to the wrong person."

The school apparently lasted only three years, but produced what Presley called "an amazing number of teachers and other prominent people." He added: "It was probably the best school in White County at the time."

Connie Patterson said that they school was good and that it was sometimes called a "college." She said that Clay may have peaked as a town about the time when that school was operating. She was an infant when it closed.

For entertainment when she was growing up, there were lots of singings. "We had an organ, and the older girls played," she said. "We sang songs like ‘Red River Valley’ and ‘When You and I Were Young, Maggie.’ And there were parties where we played musical games."

Baseball was a big sport, and Clay’s Dick Adcock was a left-handed pitcher with a good curve ball. He pitched for the Arkansas Travelers and for several St. Louis Cardinals farm teams. He once struck out Babe Ruth in an exhibition game.

He had winning records like 25-5 for Augusta, Ga. He got as far as Atlanta, when it had a Cardinals farm team, but never made it to the majors. He said he was born too soon to cash in on his talent.

After an injury curt his career short, he returned to Clay to farm. He managed a local team that competed with other county teams. "He played first base," Ken Smith, a Clay resident, said. "We tried to get him to pitch, but he wouldn’t."

The village part of Clay is gone. All the stores except one have disappeared and it has been closed for perhaps 40 years or more. The houses that were close to the stores have also disappeared.

Other homes have been built in the community, and the loss in population may be small. The farms are still there, and hay and cattle grow where cotton used to reign as the big cash crop.

A project that has occupied residents in the ‘90s is the Howell Cemetery. It was overgrown with briars, vines and other vegetation until a cemetery board was formed and people went to work.

Funds were raised to erect markers for unmarked graves or those marked only by flat field stones. Efforts are being made to identify all the people buried in the cemetery. Glen Majors says that an estimated 150 to 200 persons buried there have yet to be identified.

Every April and September work days are held to clean the cemetery. People have come from as far away as Jonesboro to help.

Among the people buried in the Howell Cemetery is Abram Shelby, a first cousin of President Martin Van Buren. He was the father of Mrs. Dudley Howell, J.J. Howell’s sister-in-law.

Another grave belongs to a black woman who was a slave before the Civil War. After she was freed, she refused to leave J.J. Howell. A cemetery report says: "She stayed on and cared for Mr. Howell in his ailing years."