| T |

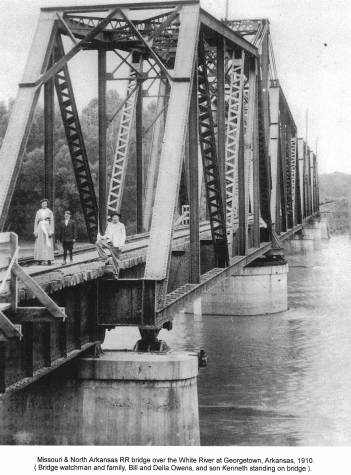

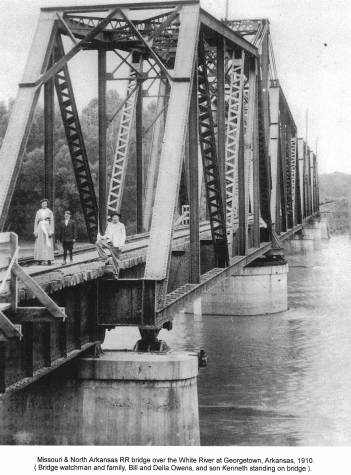

he Georgetown bridge over White River was featured in the 2002 Winter edition of Oak Leaves, the historical journal of the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad published by the Boone County Historical & Railroad Society. The photographs were provided by White County Historical Society member Pauline “Polly” Cleaver of Georgetown. She identified the family as Bill Owens, his wife Della and son Kenneth, photographed in 1910. Bill is holding an oil can with a U-shaped spout in both photos. In the view taken at their Georgetown home, Della is holding a large turnip or head of cabbage, and Kenneth has his pet pig at his side. The following is reprinted from the Winter issue:

Q - Our cover shows the end of the bridge that had the water tank, but is it the north end or the south end?

I checked all of the timetable reproductions I have, hoping that one might indicate Water Tank at N or S end, but none do... The North Arkansas Line tells us that the bridge was in service in 1909. Wisconsin Bridge and Iron erected two 125-foot through-truss fixed spans, a 300-foot through-truss turn span, and a 60-foot deck plate girder approach span, but no indication of which end had the deck plate girder. Thinking that there might be some standard for this “left bank – right bank” thing, I called the Army Corps of Engineers in St. Louis. I was told that the designation is determined by looking downstream… If I’m right about this, water tank and deck girder were on the south end of the bridge.

Back to the photos: The bridge looks good, don’t see rust splotches or peeling paint, so perhaps within a few years of construction. The oil can is prominent in both photos, so it must have some importance, at least to the Bridge Master, a sort of scepter in his hand. The wife’s clothes seem to be the same in both photos, white sash around waist, hair same style, with the land in his Sunday best, so guessing both were taken on the same day. Pictures seem to be professionally done, not snapshots, so maybe railroad photographer? At home, the lady is proud of her produce, Bridge Master has taken off his fedora and put on a more official-looking cap, but same light-colored jacket and sort of baggy pants.

Q – Was this a house owned by the railroad and provided with the $12.50 per month wages?

I would think you would want your man in close proximity to his duty station.

Q – Hours? It would seem to be a seven-day-a-week job, from sunrise to sunset.

A reading of Steamboats And Ferries On White River by Sammie Rose, Pat Wood, Duane Huddleston, UCA Press, Conway, AR, 1995, steamboats seemed to find a place to tie up at dusk, getting under way again at daybreak. It seems there were enough snags, snares and sandbars to struggle with during the day, without braving the twists and turns with poor illumination at night. Steamboats didn’t run on schedules like trains, where the Bridge Master could say, “Okay, that was the Tuesday downstream at 3:00 PM; there won’t be another until the 9:00 AM upstream on Thursday, so I can go home.” While a few packet companies owned several boats, many, if not most, were independently owned and came and went as the owner-Captain saw fit.

Q – How was the bridge turned? Gasoline and kerosene engines were in use in 1909 but how easy were they to start? How reliable?

If either were used, I’d think a back-up manual system was in place, and perhaps it was strictly manual, with that being the reason for the oil can. (I don’t think electricity would have been an option then.)

Q – Procedure?

I would presume the Captain of the boat would “blow” for the bridge. If coming upstream, slow the paddles to hold position against the current, as the boat waits for the bridge to turn. If downstream, reverse the paddles and power as needed so the current doesn’t carry you into the bridge. Was there some signal (via flag or lantern) given to the boat in acknowledgement of the “call” for the bridge?

Q – Was there some sort of latch-lock device on each end of the turn-span rails, to keep them in precise alignment? (Such would seem to have been desirable.) If yes, would the Bridge Master scurry the 150 feet to one end, undo the device, then hustle the 300 feet to the other end to do likewise, then back to the center to begin the turning? Would he then try to start an engine, or just start cranking?

Q – Was there some sort of signal for the railroad to show that the span was open?

From Timetable #7, September 4, 1927: D15. Draw Bridges – White River bridge No. 293-0. All trains will approach this bridge under control and be prepared to stop, if flagged by the watchman. If not flagged trains may proceed over bridge at a speed not to exceed 5 MPH until entire train has passed over, but it will not be necessary to come to a full stop. Rear brakeman on both freight and passenger trains must be in a position to give proceed signal after rear of train has cleared bridge.

From Timetable #2, March 27, 1938 under section entitled SPEED RESTRICTIONS: Draw Bridge – All trains will approach White river bridge (draw span) MP 293.0 under control prepared to stop; will proceed only when it is known draw span is in proper position and the way is known to be clear. If stopped by flagman, will proceed only upon instructions of or upon signal from flagman. Freight trains will reduce speed to 10 MPH over approaches to river bridge and 5 MPH over steel span; Passenger trains will reduce speed and run carefully over this structure. Trainmen of all trains must be in position to give proceed signal to engineer after rear of train has cleared bridge.

Both of the above are all well and good, but I don’t know how that poor “flagman” takes care of it from out there in the middle of channel, unless he faces the direction of the approaching train and waves a big flag like crazy. (I thought they might use some sort of “smash board” to throw across the tracks as the latch-lock device was undone, but no mention of such.)

Q – Weather Protection – I don’t see any sort of cubicle or enclosure in the center of the turn-span, at the point where the turn mechanism would be, to keep the man on duty out of the wind and rain.

Maybe a shanty near the water tank?

Q – How long was the M&A required to have a man present to turn the bridge if needed?

If the White River was still considered to be a navigable waterway and under the jurisdiction of the Corps of Engineers, perhaps it was required until operations ceased in 1946. It is possible that it could have been left open after that.

The Georgetown bridge was damaged during flooding in April of 1927 and the pier never seemed to be right after that. Today the bridge is gone. Of all the through truss bridges between Leslie and Cotton Plant, the White River bridge was the only one removed when the line was abandoned. Oak Leaves is published three times a year and distributed free to members of the Boone County society. Memberships are $15 a year and may be obtained at BCH&RR, P.O. Box 1094, Harrison, AR 72602-1094.