Remembering the Rialto

By RAY W. TOLER

As I was growing up in the 1930s in Searcy the Rialto Theater played an important part in my life. To start with, when I walked out the front door of my home at Spring and Academy streets I could see the rear of the imposing brick building in which I spent many enjoyable hours. For as long as I could remember, there was a theater on the northwest corner of Spring and Race streets. The Rialto began as the Grand, which was the first theater in Searcy. The original Grand was torn down in 1923 and a new one constructed at the same location. After a facelift in 1929, it was given the name of the New York theater district then being adopted all over America, “The Rialto.”I could buy a five-cent Black Cow sucker at Sanitary Market and make it last all Saturday afternoon at the Rialto. The first movie I remember in any detail was “All Quiet On The Western Front” released in 1930. Then there was another film involving Roman chariots. But the most thrilling to me were the westerns starring Tom Mix, Bob Steele and William Boyd (Hopalong Cassidy) who arrived on the silver screen about 1936. This was the era of Pathe newsreels, one-reel comedies and western serials. A prime example of the later involved a wolf man who emerged at night from a secret compartment of a sales counter in a western general store. Episodes were typically 13 in number and I could hardly contain myself waiting for the identity of the wolf man, or some similar thrilling climax in episode 13. In about 1935 the Charlie Chan movies made it to the silver screen with Warner Oland in the title role. In about 1940, Sidney Toler, no kin, replaced Warner Oland. In all, about a dozen Charlie Chan movies were produced, and I saw every one that came to the Rialto.

Comfort was a big drawing card. The Grand had been advertised in the summer as the place “where the typhoon breezes flow.” A unit that took air from outside and forced it through the building created a constant breeze, which was a welcomed relief before the days of air conditioning. One day in 1931 as I was walking to town I observed construction activity on the rear wall of the theater building. The crew was making two large openings far up the wall. As the work progressed over several days I learned, as sidewalk superintendent, that the Rialto Theater would soon be “air cooled,” and I was first in town to know. The process was a series of nozzles spraying a fine water mist and large fans to deliver the cooled air to the seating area.

At one time in the checkered history of the Rialto the

W.E. Blume family managed the enterprise. Mr. Blume, who had been named manager of the old Grand back in 1918, was

still in charge of the Rialto during my boyhood while Mrs. Blume sold tickets

from a booth out front. Son Jack took

up tickets and daughter Lucylle presided at the popcorn machine. Years later, the Blumes operated a thriving

popcorn business on the west side of Courthouse Square.

At one time in the checkered history of the Rialto the

W.E. Blume family managed the enterprise. Mr. Blume, who had been named manager of the old Grand back in 1918, was

still in charge of the Rialto during my boyhood while Mrs. Blume sold tickets

from a booth out front. Son Jack took

up tickets and daughter Lucylle presided at the popcorn machine. Years later, the Blumes operated a thriving

popcorn business on the west side of Courthouse Square.

To me the most important staff member at the Rialto was the projectionist. I made it a point to talk to Mr. Allen Cooke at every opportunity. Eventually I was invited into the projection booth located above the lobby. What a magical place! The small room was dominated by two huge floor-mounted projectors tilted downward and aimed at the screen. The machines were labeled “Simplex” which belied the nature of the beasts. Mr. Allen showed me how he mounted the reel and threaded the film through the many sprockets, idler rollers, frame shutter, frame-centering gate and on to the take-up reel. Two important controls were frame centering and focus. I was shown where the arc light was generated, the sound track pilot light and photocell. On the floor near one wall was the motor-generator set that furnished direct current for the arc lights and pilot lights. One complicated mechanism was for advancing the arc light carbons as they were gradually consumed in the arc. For some reason I had the gall to ask why the two carbons were of different diameters. Mr. Cooke very patiently explained that if they were the same diameter, one carbon would be consumed faster than the other. Having carbons of different diameter allowed changing both carbons at one time.

Mounted on a workbench was the reel rewinding and film splicing station. To the side on a shelf were the amplifiers for the sound system. The house lights switches were also in the projection booth.

On one visit to the projection booth, Mr. Cooke instructed me in the fine art of reel continuity. Then I realized the necessity of two projectors. In a multi-reel movie the process went like this:

1. When the reel in projector number one was within a minute or so from the end, the arc light in projector number two was started. 2. Within about five to 10 seconds from the end of the reel in projector number one, as determined by a spot flashed on the screen in the upper right corner, projector number two was started. 3. Immediately upon appearance of the second marker spot, the projection shutter on projector number one was closed and, simultaneously, the projection shutter on projector number two was opened. This operation was critical for a smooth transition from reel to reel, and Mr. Cooke was a master at it. I daresay the average moviegoer never saw the marker spots and never knew when one projector was started and the other stopped. Some of the reels did not have marker spots, but Mr. Cooke was undaunted. He merely unwound the film to suitable locations and made his own spots by gently scraping the film emulsion with his pocketknife. 4. With projector number two successfully started, the arc light in number one could be shut down and the film could be rewound. Also, in this interval the carbons in number one could be replaced if necessary. After the movie was over and house lights were turned on the last reel could be rewound and placed in its can. By this time the projectors had cooled down enough to permit polishing of the arc light parabolic reflectors and cleaning of lenses.I should mention that Mr. Allen had tattoos and sported a mustache. There were rumors that he had been “carney” and had spent some time in the Navy. At any rate, he was a skilled operator and I admired how he kept the projector machinery oiled and adjusted. He kept clean towels in the floor of the projector housing to absorb excess oil. He once advised me “Oil is cheaper than machinery.”

Various promotions were tried at the Rialto to increase business. I recall vaguely that dishes and maybe kitchen utensils were involved. One promotion involved chances on a wheeled rocking horse valued at $80. I had the lucky ticket but was too old to enjoy it. I suspect my mother sold it in one of her rummage sales.

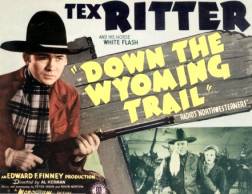

One of the promotions I recall vividly was the personal appearance of Tex Ritter. He sang “The Boll Weevil Song” and probably others. Another promotion was exhibition of a Cord automobile parked in front of the theater. The Searcy High School Band, of which I was a member, played for Easter Sunday services at the Rialto.

In the fall of 1940, when I left Searcy and the Rialto for college, the old marquee was torn down and a new one installed. The five-colored, 67-foot sign was designed with 300 feet of neon tubing, making it the largest neon sign in White County. In 1946 a new sound system was installed and in ’49 the Rialto entrance and ticket office were lowered to sidewalk level to make room for an enlarged concession bar and additional seats. Then air conditioning was added in 1953. I’m happy that the Rialto is still entertaining the community, and I always drive by for a look when I come home to Searcy. Although my career took me away to other towns, I never forgot the good times at the Rialto.

vvv

(The writer is a member of the White County Historical Society.)